Blanca Villuendas on Dream Interpretation in Islam, An Overview

Written on November 25th, 2021 by Blanca Villuendas

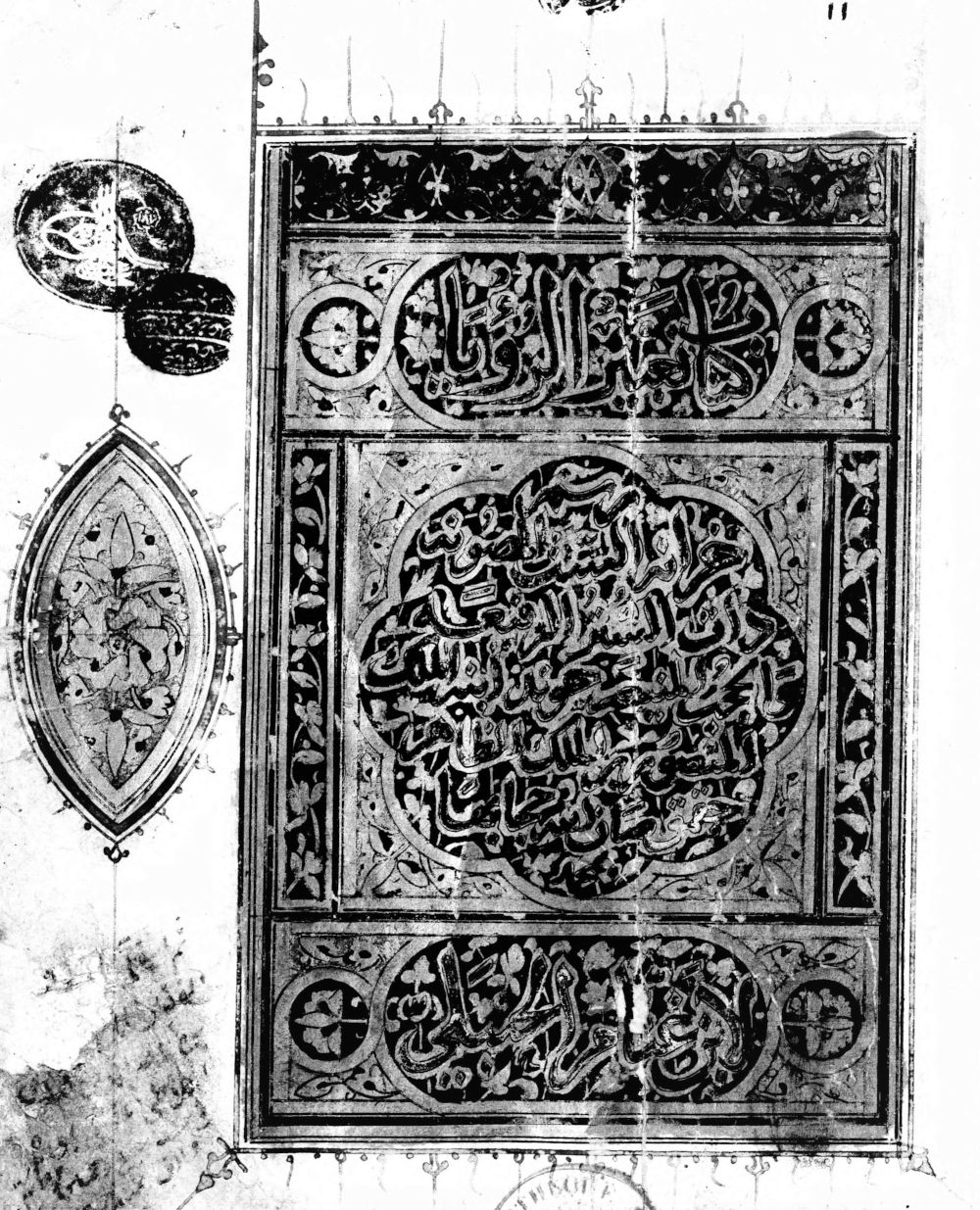

Dream interpretation is known in Arabic as taʿbīr al-ruʾyā (interpretation of dream visions) or tafsīr al-aḥlām/al-manām(āt) (explanation of dream/s), and less commonly taʾwīl al-ruʾyā (interpretation of dream visions). Traditionally, it has been regarded as one of the religious sciences and the subject of an abundant literary production, especially in the format of dream books.

The interpretation of dreams plays a relevant function in the Quranic revelation, especially if one considers that initially the Prophet received it during his sleep. Moreover, the sura of Yusuf constitutes an eloquent example of the decisive role in human affairs of godly inspired dreams and interpreters. It also provides a model for the type of oneiric experience characterized by the presence of symbols that need to be decoded through a process of interpretation.

Several sources show that the Arabian society, pre- and post-Islamic, was heavily influenced by their dreaming experiences. It was considered a reliable and accessible means to receive prophecies.1 In the historical accounts, we find both cases of speech communication with a messenger (such as the Prophet Muḥammad, an angel, or a deceased), or messages conveyed by symbols. The fore are normally self-explanatory dreams, and often their narrations picture the characteristic context of the ancient practice of incubation (in Arabic, istikhāra). Symbolic dream messages, on the other hand, are the prevalent type of dream experience present in hadith collections, which usually devote to this phenomenon an entire chapter under the title of Kitāb taʿbīr al-ruʾyā or Kitāb al-ruʾyā. These chapters comprise two major themes: On the one hand, Muḥammad’s postulates about the nature of ominous dreams, their role as carriers of glad-tidings, and how to avoid the consequence of a bad dream. On the other, examples of true dreams seen by members of the community, especially the prophet, who normally is the one to offer an interpretation, but also others like the first caliph Abū Bakr al-Ṣiddiq. To a great extent, the statements are coherent with those formularized in neighbouring traditions such as the Greek,2 or the Jewish one,3 and they are often quoted in methodological expositions related with the science of dream interpretation. Three of the assertions in the hadith allow us to understand why the interpretation of dreams enjoyed the status of ʿilm, and why already in the epistles of the Brethren of Purity it is recognized as one of the nine religious sciences (ʿulūm al-dīn), or as one of the sciences of religious law (ʿulūm al-sharīʿa), as described by Ibn Khaldūn.4 First, there is the notion that the true dream (ruʾyā ṣāliḥa or ṣaḥīḥa) is part of the revelation (juzʾ min ajzāʾ al-nubuwwa). This idea finds its parallel in the Talmud, where the proportion is quantified in one-sixtieth part (Berakhot, 57b), while in the sayings of the prophet it diverges depending on the different reports, being one forty-sixth part the most extended version.5 The connection with prophecy is reinforced by another saying in which Muḥammad states that after him the only prophecy left will be the oneiric vision (in some versions it refers first to the mubashsharāt, glad-tidings, and to the question of what glad-tidings are, he answers: the [oneiric] vision). Finally, there is the assumption that the vision of the prophet in dreams is always true. All these considerations lead to the idea that true dreams taken as divine messages are somewhat similar to the scriptures and have to be carefully interpreted. The legal experts also considered the possibility of experiencing direct communication with the Prophet in a dream and discussed the validity of the sayings or commandments transmitted in such context.6

Therefore, it should come as no surprise that the main experts in the interpretation of dreams are prominent scholars in tafsīr and traditions. These scholars base their predictions on their knowledge of the Islamic traditions, including religious and literary sources, where they find indications for the meanings of the oneiric symbols. Other times, the interpreter’s capacity of reading the signs appears to rely on some degree of inspired knowledge, typically among Sufi masters. The first in building a reputation as true interpreters (muʿabbirūn) are two hadith transmitters: Saʿīd Ibn al-Musayyib (15-94/642-715), and the most renowned dream interpreter of all times, Muḥammad Ibn Sīrīn (33-110/654–728). Allegedly, Saʿīd’s interpretative skills came from Asmāʾ, the daughter of the caliph Abū Bakr, who tought him the art; while Ibn Sīrīn would have learnt it from Ibn al-Musayyib,7 although the fact that his mother was a client of Abū Bakr may also his familiarity with dreams. Accounts of their interpretations appear in different sources following the traditional pattern of a dream narration: a dialogue in which someone explains a dream to the interpreter, who manages to interpret it correctly, as it is proved by the narrator confirming the fulfilment of the prediction. For Ibn al-Musayyib’s interpretations, we have a list in the Ṭabaqāt of Ibn Saʿd (V, 93). For Ibn Sīrīn, the main sources are al-Jāḥiẓ in his Kitāb al-ḥayawān and Ibn Abī l-Dunyā in his Kitāb al-Manām,8 as well as later dream books. Nonetheless, such anecdotes seem to have also been collected, already by the second/eighth century, in independent volumes under the title of Kitāb Ibn Sīrīn and similar.9 Despite lost, this literature would constitute the first attempts to codify dream interpretation. Yet, it has not been assessed whether this production is in any way related to the series of dream books that have been attributed to Ibn Sīrīn over the time.10

As for the personalities involved in the composition of dream books, they are distinguished scholars, who exhibit in their works a vast knowledge of the religious and linguistic lore, as well as of the tradition of dream interpretation, by adding to the existing collections their own dream symbols and meanings. One of the most import contributors is Ḥunayn b. Isḥāq (d. 264/877). His translation of Artemidorus’ Oneirokritikon, masterly adapting the contents to the worldview of a monotheist environment, had a big influence in later Arabic dream interpretation. Under the title of Kitāb taʿbīr al-rūʾyā, it became a model for subsequent dream books, many of which also bare this title and quote from it in a more or less acknowledged way. Given that the earliest preserved example of an Islamic dream book, that of ʿAbd Allāh b. Muslim Ibn Qutayba (d. 276/889), is contemporary to Ibn Isḥāq, it seems likely that even this author was influenced by him. Whatever is the case, it does not imply that there were no dream books before, since the Near eastern region had already provided very significant examples of this literature such as the so called “Assyrian dream book”, the dream book in the Talmud (Berakhot, 55a-57b) or the Somniale Danielis, a Byzantine composition dated to between the 4th and 7th centuries. However, after the Arabic version of Artemidorus, the production seems to have evolved into larger, more elaborated and organised treatises, provided with a methodological introduction and with examples of dream narrations; aspects that are rare in earlier books, but common in the Islamic production known to us.

The Islamic legacy is most widely portrayed in Fahd’s inventory of Oneirocritic authors and works.11 He counted 181 titles, reaching up to the Modern era, including also non-Muslims. In his turn, Lamoreaux provided detailed studies of the production in the early period of Islam, with 68 names. He focused first on the works by Ibn Qutayba and Khalaf b. Aḥmad al-Sijistānī (d. 398/1008), before introducing the representatives of his classification in four types of intellectuals: “the shariʿa-minded interpreter”, in the figure of ʿAlī b. Abī Ṭālib al-Qayrawānī, author of al-Mumattiʿ (or *Mumtiʿ) fī taʿbīr al-ruʾyā; “the litterateur,” represented by Abī Saʿd Naṣr b. Yaʿqūb al-Dīnawarī with his Al-Qādirī fī ʿilm al-taʿbīr, dedicated to the Abbasid caliph al-Qādir bi-Llāh (r. 381/991-422/1031); “the Sufi”, portrayed by ʿAbd al-Mālik b. Abī ʿUthmān al-Wāʿiẓ al-Khargūshī (d. c. 406/1015); and “the philosopher”, with Ibn Sīnā (d. 428/1037) with his Taʿbīr al-ruʾyā.

Despite the important contributions by Fahd and Lamoreaux, our knowledge of this production is partial. Only a few works have been published and the number of critical editions is very small. This is particularly problematic due the lack of consistency of this type of works: they are often subject to changes and rearrangements. Furthermore, we should take into account that already in the eleventh century al-Ḥasan b. al-Ḥusayn al-Khallīl listed in his lost Ṭabaqāt al-muʿabbirīn more than 7500 interpreters of dreams, which tells us about the size of the production.12

Nowadays, dream interpretation is generally less appreciated as a religious science than before, but is still accepted by many, who consider it the only valid form ʿilm al-ghayb.13 Dreambooks are well represented in bookstores, mainly under the following titles: the Muntakhab al-kalām fī tafsīr al-aḥlām by Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn b. al-Ḥasan al-Dārī, falsely attributed to Ibn Sīrīn; Al-Ishārāt fī ʿilm al-ʿibārāt by Gars al-Dīn Khalīl Ibn al-Shāhīn (d. 872/1468); and, in particular, the Taʿṭīr al-anām fī tafsīr al-aḥlām by ʿAbd al-Ganī al-Nābulusī (d. 1143/1731), which has been transformed into mobile applications. To these titles some modern contributions can be added.14 Furthermore, the practice is alive through an oral transmission, typically carried out by women.15

Author bio

Blanca Villuendas is a Juan de la Cierva Post-doctoral researcher at the University of Barcelona, working on intellectual history in the Islamicate world. Her contributions are devoted to the study of Arabic and Judeo-Arabic sources, tracing their history and transmission, and to the production of critical editions. She is interested in examples of global traditions that challenge religious and cultural identities. For this reason, her main focus has been divinatory sciences like geomancy and dream interpretation from an interreligious perspective. Another of her interests is manuscripts studies, a field in which she is actively involved with her participation in the digital humanities project “The History of the Jewish Book in the Islamicate World”, lead by Judith Olszowy-Schlanger (University of Oxford) and Ronny Vollandt (LMU), and funded by the DFG and the AHRC.

Sources

First image: Muhammad’s call to prophecy and the first revelation, from a Majmaʿ al-Tavarikh c.1425. MET DP100981.

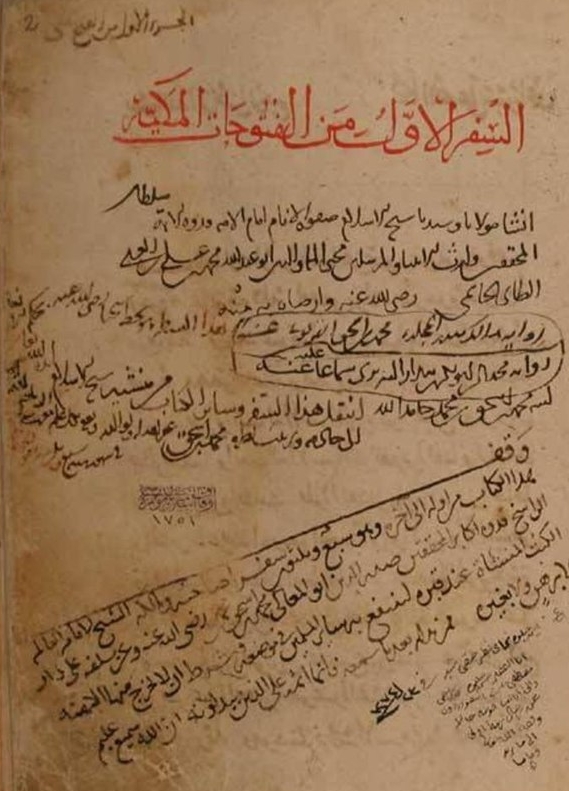

Second image: Detail of the title page of the Amiriyya copy of the dream book of Ibn Ghannām. MS BNF Arabe 2751.

Al-Dīnawarī, Kitāb al-taʿbīr fī-l-ruʾyā = Al-Qādirī fī-l-taʿbīr, ed. F. Saʿd, (Beirut: ʿAlam al-Kutub, 1997).

Ibn Isḥāq, Le livre des songes (Kitāb Taʿbīr al-ruʾyā), ed. T. Fahd, (Damascus: Institut Français de Damas, 1964).

Ibn Qutaybah, Kitāb Taʿbīr al-ruʾyā. Ed. I. Ṣāliḥ, (Damascus: Dār al-Bashāʾir, 2001).

Ibn Šāhīn, J. Al-Išārāt fī ʿilm al-ʿibarāt, ed. de K. Hasan, (Beirut: Dar al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiya), 1993.

Ibn Sīrīn, Tafsīr al-aḥlām al-kabīr: Muntajab al-Kalām fī Tafsīr al-aḥlām, ed. de U. M. Al-Sayyid, (Beirut, Muʾassasat al-Kutub al-ṯaqāfīya, 1993.

Further reading

ʿAbd Allāh Abdel Daïm, L’oniromancie arabe, d’après Ibn Sîrîn, Damascus: Presses Universitaires, 1958.

Muhammed Abdul Muid Khan, M. Kitabu Taʿbir-ir-ruya of Abu ʿAli b. Sina, Indo-Iranica, (1956) 9: 43-57.

Nathaniel Bland, “On the Muhammedan Science of Tâbīr, or Interpretation of Dreams,” JRAS 16: 118-71 (1856).

Toufic Fahd, “La traduction arabe de l’Oneirocritica d’Artémidore d’Éphèse,” Arabica 7 (1): 87-89 (1960).

Toufic Fahd, “Hunayn Ibn Ishaq est-il le traducteur des Oneirocritica D’Artémidore D’Éphèse?”, Arabica 21 (3): 270-84 (1974).

Nile Green, “The Religious and Cultural Role of Dreams and Visions in Islam,” JRAS 13: 287-313 (2003).

Pierre Lory, Le rêve et ses interprétations en Islam, (Paris: Albin Michel, 2003).

Huda Lutfi, “The Construction of Gender Symbolism in Ibn Sīrīn’s and Ibn Shāhīn’s Medieval Arabic Dream Texts,” Mamluk Studies Review (2005) 9 (1): 123-163.

Miklós Maróth, “The Science of Dreams in Islamic Culture,” Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam (1996) 20: 229-236.

Maria Mavroudi, A Byzantine book on dream interpretation: the Oneirocriticon of Achmet and its Arabic sources, (Boston-Leiden-Köln: Brill, 2002).

——— “Taʿbīr al-ruʾyā and Aḥkām al-nujūm: References to Women in Dream Interpretation and Astrology Transferred from Graeco-Roman Antiquity and Medieval Islam to Byzantium: Some Problems and Considerations,” Classical Arabic Humanities in Their Own Terms (2008): 447-467.

——— “Byzantine and Islamic Dream Interpretation: A Comparative Approach to the Problem of ‘Reality’ vs. ‘Literary Tradition’,” in G. T. Calofonos (ed.), Dreaming in Byzantium and Beyond, (Surrey: Ashagte, 2014): 161-186.

Amira Mittermaier, “The Book of Visions: Dreams, Poetry, and Prophecy in Contemporary Egypt”, Journal of Middle East Studies (2007) 39 (2): 229-247.

Adolph L. Oppenheim, “The interpretation of dreams in the Ancient Near East, with a translation of an Assyrian Dream-Book,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series (1956) 46 (3): 179-373.

Bronislav Ostřanský, “The Art of Medieval Arab Oneirology,” Archiv Orientální (2005) 73: 407-428.

M. Rezvan, “‘If somebody dreams about reading the Qur’ān, it is a good dream’ (On the modern interpretation of the medieval tradition),” Manuscripta Orientalia (2004) 10 (4): 34-37.

Elizabeth Sirriyeh, “Dreams of the holy dead: traditional Islamic Oneirocriticism versus Salafi Scepticism,” Journal of Semitic Studies (2000) 45 (1): 115-130.

——— “Muslims Dreaming of Christians, Christians Dreaming of Muslims: Images from Medieval Dream Interpretation,” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations, (2006) 17 (2): 207-221.

——— “Arab stars, Assyrian dogs and Greek ‘angels’: how Islamic is Muslim dream interpretation,” JIS (2011) 22 (2): 215-33.

Blanca Villuendas Sabaté, “Dream Interpretation Reinterpreted in the Light of Judaeo-Arabic Fragments Attributed to Hai Gaon,” *Unveiling the Hidden-Anticipating the Future: Divinatory Practices among Jews Between Qumran and the Modern Period”, ed. J. Rodríguez-Arribas (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2021): 140-160.

——— Onirocrítica islámica, judía y cristiana en la Gueniza de El Cairo: edición y estudio de los manuales judeo-árabes de interpretación de sueños (Madrid: CSIC, 2020).

——— “Interpreting Islamic Dream Books of the Cairo Genizah: The Taʿbīr al-ruʾyā and Its Judeo-Arabic Witnesses”, Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 8 (2020): 306-42.

-

For an analysis of prophetic dreams from the early period of Islam see Fahd, Toufic La divination arabe: études religieuses, sociologiques et folkloriques sur le milieu natif de l’Islam (Leiden: Brill, 1966), 247-367. ↩

-

For example, according to the dream manual of Artemidorus of Daldanis, the Oneirokritikon, and partially to Aristotle in his On Divination. ↩

-

In particular, in the chapter “Ha-Roʾe” of the tractate Berakhot of the Babilonian Talmud. ↩

-

Ibn Khaldūn. The Muqaddimah, trans. F. Rosenthal, (London: Routledge, 1958), ***. ↩

-

See Ibn Ḥajar, Fatḥ al-bārī fī sharḥ Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī, ed. Ibn ʿAbd al-Bāzz (Beirut: Dār al-Maʿrifa, 1960), vol. 12, 362-8, for a complete account on the different proportions collected in the different version of the hadith. ↩

-

See Leah Kinberg, “The legitimization of the “Madhahib” through dreams,” Arabica 32 (1985): 47-79. ↩

-

See John C. Lamoreaux, The early Muslim tradition of dream interpretation, (New York: SUNY Press, 2002), 23. ↩

-

See Leah Kinberg, “Dreams” ***. ↩

-

See Lamoreaux, The early Muslim tradition of dream interpretation, 22. ↩

-

For a brief account of these titles, see Fahd, Divination Arabe, 355-6. ↩

-

See Divination Arabe, 330-63. ↩

-

See Lamoreaux, The early Muslim tradition of dream interpretation, 17-8. ↩

-

See I. R. Edgar, The dream in Islam: from Qur’anic tradition to Jihadist inspiration, (New York: Berghahn Books, 2011). In the Internet, one can find many examples of people asking religious authorities whether dream interpretation is a form of ghayb and whether or nor is acceptable. The ones I have read receive a yes for both questions, considering dreams the only way through which God is offering the believers some knowledge of the future. See for example the website Al-islām suʾāl wa-jawāb. ↩

-

For example, ʿA. Ḥ. Al-ʿAfīfī, Al-Aḥlām wa-l-kawābīs: Tafsīr ʿilmī wa-dīnī, (Cairo: Dar al-Misriyya al-Lubnaniyya, 1993). ↩

-

See Araceli Gonzalez-Vazquez, “Dreaming, dream-sharing and dream-interpretation as feminine powers in northern Morocco”, Anthropology of the Contemporary Middle East and Central Eurasia (2014) 2 (1): 97-108. ↩