Łukasz Piątak on Astral Worship in al-Suhrawardī’s al-Wāridāt wa'l-taqdīsāt

Written on January 2nd , 2023 by Łukasz Piątak

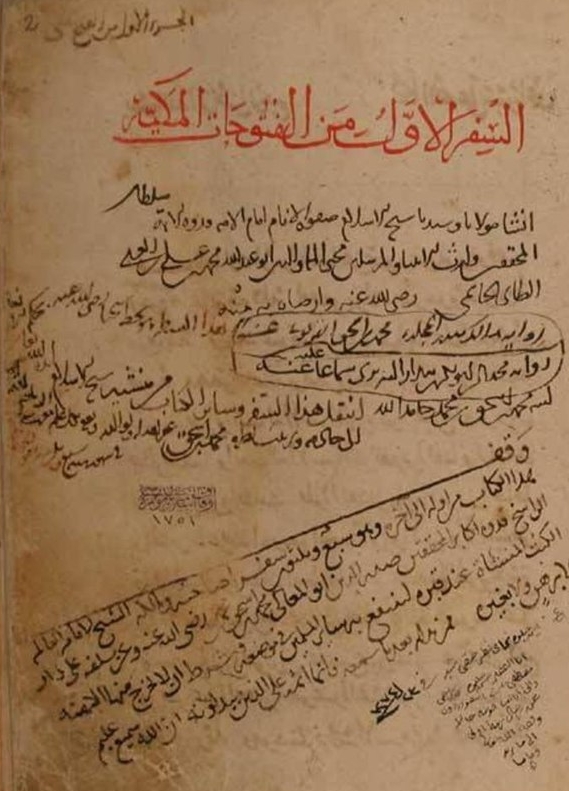

This piece provides a sample of some issues tackled in my doctoral dissertation entitled “Between Philosophy, Mysticism and Magic: A Critical Edition of Occult Writings of and Attributed to Shihāb al-Dīn al-Suhrawardī (1156-1191)”. In the thesis I attempted to confirm his authorship of a work entitled Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt (Divine inspirations and sanctifications) arguing the possibility of Illuminationist liturgy devoted to beings of light and prominently among them the planets.

Possible occult elements in al-Suhrawardī

There is a number of Occult features in the thought and biography of al-Suhrawardī as it is found in sources, that have been pointed to in the scholarship. Among them one may enumerate his theory of ancient wisdom (al-ḥikma al-‘atīqa)1, elements of astrology and alchemy occurring in his visionary recitals2 as well as the image of al-Suhrawardī as a sorcerer in chronicles and biographical compendia3. I propose to add to this list his puzzling claim of yet another book being divine- or semi-divine revelated, apart from the Qur’an. It is not clear whether it refers to his opus magnum Ḥikmat al-Ishrāq or Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt4 or the mysterious ‘Hermethical inscription’ (raqīm Hirmis) that he mentions in the latter5. Another, perhaps the most evident issue, which is elaborated almost exclusively on in Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt is the one of astral worship as a part of veneration of lights.

Brief characteristics of al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt

Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt is a work of medium size written in Arabic. It consists of 15 or 16 independently titled chapters. In accordance with the main title of the book they can be divided in two groups: revelatory ‘divine inspirations’ (al-wāridāt) and liturgic ‘sanctifications’ (al-taqdīsāt). The chapters from the first group combine a wide range of topics: the hierarchy of ontological lights, soteriology and ethics. Some of its passages seem to be records of visions experienced by a mystic. On the other hand, the chapters from the second group take the shape of litanies directed at a plethora of luminous entities including most prominently the planets. The structure of the oeuvre is even more intricate as the chapters and even their specific sections vary in terms of the speaking person. At times it is “the leader of illumination” (qā’id al-ishrāq) who might be associated with al-Suhrawardī himself, another time it is a third person neutral narrator or even God himself speaking in first person. The same applies to the addressees.

Rationale behind the veneration of lights

Outside Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt we find sparse but interesting mentions of veneration of lights in remaining works by al-Suhrawardī. In Al-Alwāḥ al-‘Imādiyya the legendary Persian king-sage Kay Khusraw is said to have renewed the tradition of “glorifying the holy lights” (ta’ẓīm al-anwār al-muqaddasa)6. Inclusion of this figure amidst the ranks of transmitters of the ancient wisdom, which the author claims to be its contemporary representative suggests that he is fond of such tradition. And indeed in Ḥikmat al-Ishrāq he says explicitly that all the lights ought to be praised (wājiba al-ta’ẓīm) according to the Law commanded (shar’an min Allāh) by God, the Light of Lights7. The astral worship as such appears in one passage, where Hūrakhsh, the personified soul of the sun, is ought to be obligatory venerated by “the Illuminationists”, who are most probably the disciples of al-Suhrawardī. The same fragment explains that the planets are active intermediaries, the absolute organs, by which the higher ontological lights and from behind them ultimately the Light of lights exercise their authority in the sublunary realm8. In Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt the order to venerate of lights is described as being written already in the ancient ‘Hermethical inscription’ thus being a part of a primordial revelation sent to mankind9. God himself, who is the speaker in the fourth chapter promises in return attaining illumination as well as resurrection in the higher realms10.

Call for veneration of planets

On the pages of Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt we find several calls for veneration of planets. The very opening words of the oeuvre exhort to worship the sun: Sanctify (qaddis) God and the Greatest Luminary (al-nayyir al-a’ẓam) on one of two horizons and pronounce remembrance (dhikr)11. In Wārid al-Anwār (The Divine Inspiration of Lights) the sun is referred to as ‘the image of [divine] majesty’ (mithāl jalāl). The same chapter elucidates on seven planets that ought to be praised in laudatory hymns (tasābīḥ) to gain blessings. Venerating them as creation is a part of worshiping their Creator12.

Verbal elements of liturgy: sanctifications (taqdīsat)

The liturgy of astral worship consists of verbal as well as non-verbal elements. The first are represented by the sanctifications or litanies that constitute an important part of Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt. There are 9 fragments of this character: the litany to all the levels of luminous beings, the litany to the light of lights and seven consecutive litanies to seven planets for specific days of the week. Every one of the seven prayers may be divided into eulogic and supplicatory segments. Every segment consists of very specific invocations appearing in an established order. The eulogic part comprises initial greeting, apostrophic exclamation, Persian name of the planet, numerous epithets, the laudation of planetary body and its immediate cause (the planetary soul) and eventually glorification of God. The supplicatory part usually begins with a plea to a planet in question to facilitate one of the soul’s activities, then all the intermediaries (the dominant lights including Active Intellect and Bahman) between human soul and the Supreme Being in the ontological hierarchy are asked to bring the illumination to the invocator and help in the transfer of his soul to the presence of Light of lights. The verbal part of the procedure ends with final doxology pleading for the divine support and sanctification for the “people of light” (ahl an-nūr), i.e. the illuminationists13.

Between litanies and Ghāya

A comparison between the litanies from Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt and from the Ṭabarian material of the famous early Arabic grimoire Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm (The End of the Sage) ascribed more recently to al-Qurṭubī14 shows that four on seven planetary litanies (Mars, Jupiter, Mercury, Venus) by al-Suhrawardī share many of the epithets with their counterparts from the latter. The similarities are all in the eulogic parts and pertain to how the planets are invoked and described. They may reflect the overall image of a planet in question according to astrological and mythical lore. There is however a small concession - for Shaykh al-Ishrāq all the planets are provided only with excellent virtues, so Mars is bereft of evil and hypersexual traits present in Ghāya. We cannot exclude Ghāya or the lost work of Al-Ṭabarī the astrologer as the source of these descriptions, especially in the face of possibility of even stronger relation of the subsequent section of Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt to aforementioned material. The supplicatory parts are in turn unrelated since the Suhrawardian litanies aim at pursuing the spiritual path towards the light by means of aforementioned pleas going through all levels of cosmic hierarchy, whereas in Ghāya they are focused on clearly materialist and down-to-earth boons such as love, money, power and defeating the enemies.

Non-verbal elements of liturgy. Faṣl (16th chapter) and its dubious authorship

The non-verbal elements of liturgy presented in Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt are twofold. First, the text abounds with direct indications and undirect allusions to such categories as time and place that in my opinion enable to reconstruct the stages of the ritual to be performed. Second, the last chapter entitled Fa$ṣl\ $in the manuscripts deals with astral magic aiming at subjugating the planets with the use of special non-verbal elements. It contains a description of seven rituals including mostly needed accessories: a kind of garment, a ring often with a precious stone and incense-burner and recipe for an incense. The rituals are to be performed supposedly while invoking the planetary spirits with the use of aforementioned litanies.

Yet there is a problem with the authorship of this part since virtually all the descriptions turn out to be word-to-word borrowings from Ghāya (with the exception of incense recipe devoted to the moon). In a word Faṣl does not contain any original material therefore it is uncertain whether it should be treated as integral part of Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt or not. But there is still something puzzling to it as the descriptions in Ghāya are by no mean original. Even the author or compilator of this famous grimoire admits it by ascribing the material in question to Ṭabarī the astrologer15. By comparing the Latin text of Liber de Locutione cum Spiritibus Planetarum attributed to Hermes with the corresponding material from the seventh chapter (faṣl) of the third treatise (maqāla) of Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm David Pingree succeed at establishing exactly which of its fragments are borrowings from the lost Arabic original of Ṭabarī, that he believed was the archetype of Liber16. These are precisely the same fragments that were with some omissions added as Faṣl to Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt. Moreover, Ṭabarī’s suffumigation recipe devoted to the moon, that is omitted in Ghāya, surprisingly appears in the text attributed to al-Suhrawardī. This is why it is more probable that the borrowings were done from the now-lost work of Ṭabarī than from Ghāya itself. If so, who and why has added Faṣl to of Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt? Was it al-Suhrawardī or someone else? For now we have to at least state that the Faṣl is not of Suhrawardian authorship.

Contexts in the background

Without going into details I want to signal some of the contexts that may lie in the background of al-Suhrawardī’s Occult enterprise and should be taken in consideration while interpreting his entire project. The idea of astral influence and planetary beings as efficient causes of the changes in sublunar world as well as a possibility to manipulate them through invocations and talismanic items is compatible with theories of astral causality by Abū Ma’shar (787-866) and astral magic by al-Kindī (801-879) and the author of Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm17.

There are many elements of cosmology as outlined by al-Shahrastānī (1086-1153) and even technical terms in his account of beliefs of Sabeans from Ḥarrān that show striking similarity to what can be found especially in Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt. The planetary spirits are engaged in constant sanctification (taqdīs) of “the God of deities” (ilāh al-āliha)18, a term which Shaykh al-Ishrāq uses denoting Light of lights. By “deities” (āliha) the planets are meant and al-Suhrawardī even uses the singular form of this term (ilāh) when invoking Saturn in one of his litanies19. Beside their philosophical ideas Ḥarrānians are reported to engage in an array of ritual practices directed at planetary spirits that comprised invocations (da’wāt) and suffumigation of incense (tabkhīr al-bukhūrāt). Other elements of ritual included place (makān), time (zamān), the clothing (libās) and precious stone (jawhar)20. The conformity with astral magic as presented in Faṣl is very clear here.

Brethren of Purity (Ikhwān al-Ṣafā’) were perhaps the antecedents of al-Suhrawardī in adopting some Sabean rituals as a part of their own “Philosophical worship” (al-‘ibāda al-falsafiyya al-ilāhiyya)21. Apart from leaving another account of Ḥarrānian practices they mention a set of rituals of their own – a series of prayers to be uttered in specific moments of the night between dusk and dawn22. In these we find similarity to al-Suhrawardī who also points to specific time staging albeit his hints are more obscure and demand interpretation.

Last but not least it is the ritual of planetary ascent, once again attributed to Sabeans from Ḥarrān, this time described by Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (1150-1209) in his Al-Sirr al-Maktūm (The Hidden Secret), which is the closest one in idea, space and time to the liturgy of Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt. After providing philosophical justification al-Rāzī presents a summary to an unidentified epistle by Abū Ma’shar where the description of planetary liturgy resembles non-verbal elements from the last chapter of Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt23. However, one major difference in relation to al-Suhrawardī is that al-Rāzī focuses more on material requisites, the course of the ceremony and establishing proper astrological conditions than the very words of invocations, which are central to Shaykh al-Ishrāq. Curiously, unlike al-Suhrawardī, al-Rāzī presents the rituals as being Sabean and nowhere does he endorse them explicitly24.

Al-Rāzī was not only contemporary but also the acquaintance al-Suhrawardī, they studied together in Marāgha and there are important parallels in their thought – they both started as Avicennians and tried to “philosophise” the Occult25. No wonder they could share their sources and fascinations with the astral worship.

Author bio

Łukasz Piątak is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies at Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland. He received his PhD from the Faculty of Oriental Studies at the University of Warsaw in 2019. His research focuses on intersections of Islamic philosophy, mys-ticism and the occult. His doctoral thesis, “Between Philosophy, Mysticism and Magic: A Critical Edition of Occult Writings of and Attributed to Shihāb al-Dīn al-Suhrawardī (1156-1191),” includes critical editions of the Shaykh al-Ishrāq’s famous but enigmatic al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt and the pseudepigraphal Sharḥ al-asmāʾ al-arbaʿīn/al-Idrīsiyya, a treatise on practical magic. This study investigates the possibility of Illuminationist liturgy, tracing influences or making comparisons between the Wāridāt and some elements of Zoroastrianism, the Hymns of Proclus and early Arabic traditions of astral magic. He is currently working on an English translation of Suhrawardī’s text for publication, as well as pursuing side co-project of a Polish translation of the Judeo-Arabic Ku-zari by Judah Halevi.

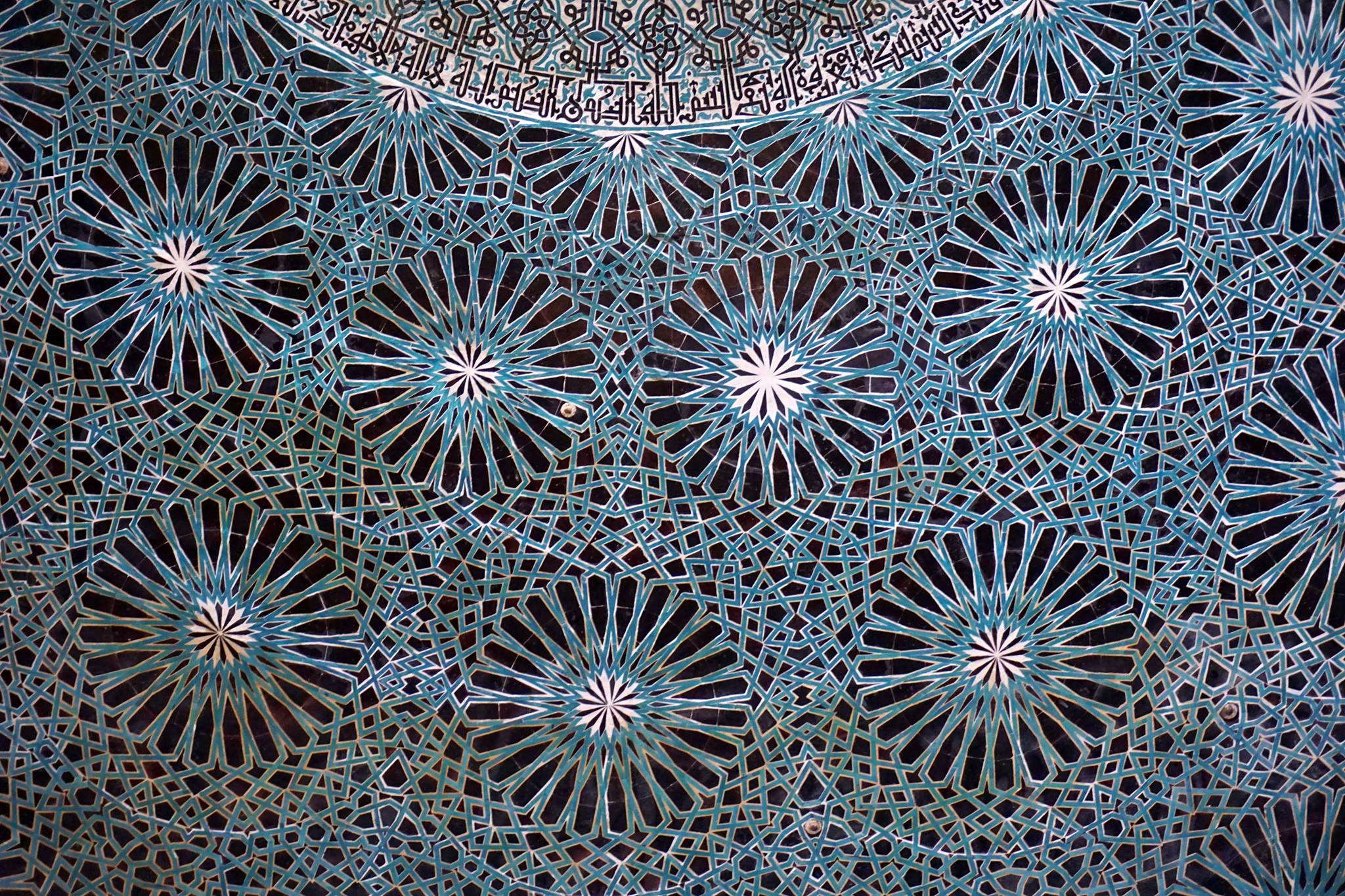

Image: The ceiling from Karatay Madrasah (built in 1250-1251), Konya. Photo by Ł.Piątak. Suzan Yalman argues that the thought of al-Suhrawardī might have influenced the use of planetary and astral symbols in the art of Seljuq of Rum26.

-

Suhrawardī, The Philosophy of Illumination, ed. John Walbridge, Hossein Ziai (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1999), 2-3. See: Sohrawardi, Ouvres Philosophiques et Mystiques. Tome I, (Téhéran: Institut d’Etudes et des Recherches Culturelles, 2001), 108, 502-503 [“Kitāb al-Mashāri’ wa’l-Muṭāraḥāt”]. On al-Suhrawardī’s theory of ancient wisdom in its both Hellenistic and “Oriental” branches see: John Walbridge, The Leaven of the Ancients. Suhrawardi and the Heritage of the Greeks (Albany: University of New York Press, 2000); John Walbridge, The Leaven of the Ancients. Suhrawardi and the Heritage of the Greeks (Albany: University of New York Press, 2000); John Walbridge, The Wisdom of the Mystic East. Suhrawardī and Platonic Orientalism (Albany: University of New York Press, 2001). ↩

-

See, for example Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila, “Suhrawardī’s Western Exile as Artistic Prose”, Ishraq 2 (2011): 105-118. ↩

-

See especially Ibn Abī Uṣaybi’a, ‘Uyūn al-Anbā’, ed. Nizār Riḍa, (Bayrūt: Manšūrāt Dār Maktabat al-Ḥayāt, n.d.), 642-4; Ibn Khallikān, Wafayāt al-A’yān, v. 6, ed. Ihsān ‘Abbās (Bayrūt: Dār Ṣādir, n.d.), 269. ↩

-

The notes pointing to Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt reference its critical edition in: Łukasz Piątak, “Between Philosophy, Mysticism and Magic: A Critical Edition of Occult Writings of and Attributed to Shihāb al-Dīn al-Suhrawardī (1156-1191)” (Ph.D. diss., University of Warsaw, 2018).The research was founded with the grant from Polish National Science Centre (“Preludium” project nr 2013/09N/HS2/02259). When referencing to Arabic text of this edition instead of pagination the number of respective section and paragraph will be indicated. ↩

-

Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt, 1:1, 1:6, 1:12-13, 1:26, 1:30, 1:36, 3:47, 3:50, 4:56, 5:66-67. ↩

-

Sohrawardi, Ouvres Philosophiques et Mystiques. Tome IV, (Téhéran: Institut d’Etudes et des Recherches Culturelles, 2001), 92 [“Al-Alwāḥ al-‘Imādiyya”]. ↩

-

Suhrawardī, The Philosophy of Illumination, [Walbridge, Ziai], 210. ↩

-

Suhrawardī, The Philosophy of Illumination, [Walbridge, Ziai], 104. ↩

-

Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt, 1:27, 3:47. ↩

-

Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt, 4:64. ↩

-

Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt, 1:1. ↩

-

Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt, 4:57. ↩

-

Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt, 7-15. ↩

-

See Maribel Fierro, “Bāṭinism in Al-Andalus. Maslama b. Qāsim al-Qurṭubī (d. 353/964), Author of the Rutbat al-Ḥakīm and the Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm (Picatrix)”, Studia Islamica, No. 84 (1996), 87-112; Godefroid de Callataÿ, “Magia en al-Andalus. Rasa'il ijwan al-Safa', Rutbat al-hakim y Gayat al-hakim (Picatrix)”, Al-Qanṭara, 34 no. 2 (2013), 297-344. Godefroid de Callataÿ & Sébastien Moureau, “Again on Maslama Ibn Qāsim al-Qurṭubī, the Ikhwān al-Ṣafā’ and Ibn Khaldūn: New Evidencefrom Two Manuscripts of Rutbat al-ḥakīm”, Al-Qanṭara, 37 no. 2 (2016), 329-372. José Bellver however in his IOSOTR speech from 12.11.2021 calls al-Qurṭubī’s authorship of Ghāya in question as he proposes to move its date to the subsequent century. ↩

-

Pseudo-Majrīṭī, Ghāyat al-ḥakīm = Das Ziel des Weisen. Studien der Bibliothek Warburg 12, ed. Helmut Ritter (Leipzig-Berlin: B. G. Teubner, 1933), 195. ↩

-

For detailed analysis of the sources of all the sections of this chapter of Ghāyat al-ḥakīm see: David Pingree, “Al-Ṭabarī on the prayers to the planets”, Bulletin d’études orientales 44, 1993, 106–107. For a wider discussion of that matter in reference to the whole work, see David Pingree, “Some of the Sources of the Ghāyat al-hakīm”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, Vol. 43 (1980), 1-15. ↩

-

See Liana Saif, The Arabic Infuences on Modern Occult Philosophy, (New York: Palgrave Macmillian), 9-45. ↩

-

Al-Shahrastānī, Kitāb al-Milal wa’l-niḥal, v. 2, ed. Aḥmad Fahmī Muḥammad (Bayrūt: Dār al-Kutub al-‘Ilmiyya, 1992), 289-294, 305, 325. ↩

-

Al-Wāridāt wa’l-taqdīsāt, 5:74. ↩

-

Al-Shahrastānī, Kitāb al-Milal wa’l-niḥal, v. 2 [Aḥmad Fahmī Muḥammad], 290. On evolution of Ḥarrānian religion see Tamara M. Green, The City of the Moon God. Religious Traditions of Harran (Leiden-New York-Köln: Brill 1992). ↩

-

Jane Mattila proposes the conceptualization through which one can understand the appropriation of Ḥarrānian rites to the liturgy of Brethren of Purity. See Jane Mattila, “The Philosophical Worship of the Ikhwān al-Ṣafā’”, Journal of Islamic Studies 27:1 (2016), 17-38. ↩

-

Rasā’il Ikhwān al-Ṣafā’ wa-Khullān al-Wafā’, v. 4, ed. Buṭrus al-Bustānī (Bayrūt: Dār Ṣādir 1957), 262-263, 272. ↩

-

For translation and a thorough study of Al-Sirr al-Maktūm see Michael-Sebastian Noble, Philosophising the Occult. Avicennan Psychology and ‘The Hidden Secret’ of Fakhr al-Dīn al-Rāzī (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter 2021). ↩

-

Michael-Sebastian Noble, Philosophising the Occult, 268. ↩

-

The term was coined by Michael-Sebastian Noble in the title of his book mentioned above. ↩

-

Suzan Yalman, “‘Ala al-Din Kayqubad illuminated. A Rum Seljuq sultan as cosmic ruler”, Muqarnas 29 (2012): 151-185. ↩