Cyril Uy on Lettrism and Epistemology in the Work of Saʿd al-Dīn Ḥamūya (d. 1252)

Written on April 10th, 2022 by Cyril Uy

This brief piece serves as an overture of sorts for a book project entitled Lost in a Sea of Letters: Saʿd al-Dīn Ḥamūya (d. 1252) and the Plurality of Sufi Knowledge. Building upon my dissertation, the project explores how medieval Sufi thinkers approached fundamental questions about knowledge: What does it mean to know? How do practices, experiences, and relationships mark people as knowing beings? How can knowledge be cultivated in writing? Thinking through these questions with medieval Sufis provokes an engagement with the embodied and experiential dimensions of knowledge production that contemporary intellectual histories typically leave unmarked.

Historical Background

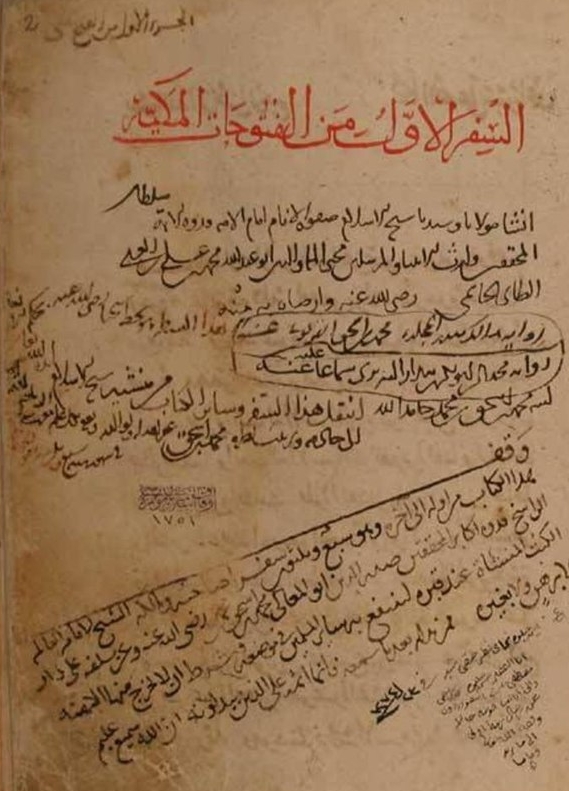

Lost in a Sea of Letters focuses on the work of Saʿd al-Dīn Ḥamūya, a 13th-century Sufi whose arcane treatises on the science of letters and the Seal of Saints both inspired and bewildered future generations of occultists, mystics, and messiahs. Born in Baḥrābād (northeastern Iran), Ḥamūya hailed from a family of powerful Sufis who claimed seats of institutional authority across Egypt and Greater Syria.1 After completing his early training in the exoteric religious sciences in Nīshāpūr and Khwārazm, Saʿd al-Dīn traveled throughout Central Asia, the Iranian Plateau, and the Eastern Mediterranean. Ḥamūya’s journeys brought him into contact with the most renowned Sufi masters of his time, including Najm al-Dīn Kubrā (d. 1220) and his khalīfas in Khwārazm, Shihāb al-Dīn ʿUmar al-Suhrawardī (d. 1234) in Baghdad, Ibn ʿArabī (d. 1240) and Ṣadr al-Dīn Qūnawī (d. 1274) in Damascus, and ʿAzīz Nasafī (d. after 1300), whom he trained upon his return to Khurāsān.2

The most enduring dimensions of Ḥamūya’s legacy were his prodigious intellectual output and the endless possibilities of his lettrist methods. Texts like The Book of the Beloved (Kitāb al-Maḥbūb) and The Mirror of Spirits and Signs on Tablets (Sajanjal al-arwāḥ wa-nuqūsh al-alwāḥ) manipulated the visual, sonic, and phenomenal qualities of the Arabic alphabet to explore the hidden recesses of Reality. Alongside numerous other treatises and a formidable collection of poetry, these esoteric tomes served as generative points of inspiration for a wide range of thinkers in Ḥamūya’s wake. ʿAzīz Nasafī framed himself as an unparalleled exegete of his master’s thought, boasting of his ability distill the arcane secrets scattered across Ḥamūya’s over four hundred treatises into just ten chapters of simple Persian prose.3 Although the Kubrāwī systematizer ʿAlāʾ al-Dawla al-Simnānī (d. 1336) rejected Saʿd al-Dīn’s theories of prophecy and sainthood, he had no choice but to engage with the shaykh’s lettrist methods in order to refute him.4 During the Tīmūrid period, the occult theorist Ṣāʾin al-Dīn Turka Iṣfahānī (d. 1432) held up Ḥamūya’s Book of the Beloved as a master key to universal knowledge, while the apocalyptic revolutionary Muḥammad Nūrbakhsh (d. 1464) marshaled the text as evidence for his own messianic claims.5 Around a century later, Maḥmūd Dihdār Shīrāzī (fl. 1576)—the Safavid occultist and teacher of Shaykh Bahāʾī (d. 1621)—cited Ḥamūya as one of the foremost masters of the science of letters and penned his Decoding Symbols in the Treasure’s Secret (Ḥall al-rumūz fī sirr al-kunūz) as a commentary on The Mirror of Spirits.6 Each of these figures and others besides them drew upon the authority of Saʿd al-Dīn’s spiritual and intellectual legacy, appropriating, challenging, and transforming his work to suit their own ideological and material goals.

Historicizing Epistemology

Despite his lasting importance in the medieval and early modern Islamic world, Ḥamūya has been largely ignored by contemporary scholarship. I suggest that this dearth of scholarly interest stems from a problem that is primarily epistemological. The rationalist frameworks that dominate intellectual history implicitly limit knowledge to logical systems that organize facts about the world. These approaches typically mine theoretical texts for propositions about the nature of reality, assembling these claims into stable metaphysical systems whose parts can then be tracked through time or stuck to specific problems for comparative analysis.

When confronted with Ḥamūya’s work, such methods hit an analytical impasse. Ḥamūya articulates complex theoretical accounts of Reality, yet subordinates rational objectivity to subjective experience. His ontological vision is not one of discrete parts and stable structures, but rather of dynamic forces whose qualities and boundaries are continually reconfigured. As he plumbs the endless possibilities of Being, Saʿd al-Dīn twists and turns through jarring non-sequiturs, recondite allusions, blatant inconsistencies, and above all, a feverish obsession with the letters of the Arabic alphabet. For him, it is not the flat surface of the page, but rather living, breathing, and speaking bodies that can encompass and reflect the inexhaustible potential of Reality. Thus, while it may be tempting to uncover a stable and neatly-bounded system beneath Ḥamūya’s enigmatic expressions, such an approach carves his work at unnatural joints, leaving us with a butchered metaphysics better suited for the wastebasket of rejected knowledge.

Lost in a Sea of Letters aims to reanimate Ḥamūya’s corpus by reading him in conversation with the work of colleagues like Ibn ʿArabī, Najm al-Dīn Kubrā, Shihāb al-Dīn ʿUmar al-Suhrawardī, and Ṣadr al-Dīn Qūnawī. Through close readings of theoretical treatises, training manuals, prayer books, teaching certificates, and personal correspondences, I excavate a medieval Sufi epistême in which even the most abstract theory was bound up with how human beings navigated material and social worlds. For Ḥamūya and his colleagues, the broader matrix of Sufi thought and practice was the only universalizing framework supple enough to subsume all other modes of knowing and being. Sufi training coupled regimented programs of social discipline and ritual practice with dynamic theoretical frameworks, producing knowing subjects that lived the world as infinite epistemological and ontological possibilities. Sufi writers in turn sought to refine how readers experienced and negotiated these possibilities, keying textual strategies to the practical and phenomenological dimensions of their embodied practices.

By identifying the practical and phenomenological strategies through which medieval Sufis communicated their abstract-experiential knowledge in text, the project expands the epistemological sensitivity of intellectual-historical methodologies and intervenes against post-Enlightenment assumptions that confine knowledge to a realm of disembodied ideas and logical propositions. Perfect knowledge here was not imagined as a mastery of facts and figures, but rather as a fluid and all-encompassing sensibility that could negotiate diverse epistemologies, identities, and practices across a plurality of contexts. In Ḥamūya’s writing, especially, this knowledge became manifest as boundless play: an undammable emanation of letters and words whose limitless possibilities could only be realized through the active engagement of qualified readers.

Bodies of Knowledge: Lettrism, Experience, and Epistemology

To illustrate Ḥamūya’s strategies in action, I offer a brief example from his Lamp of Sufism (al-Miṣbāḥ fī al-taṣawwuf). Here, the shaykh articulates what I call a “relational” approach to Reality. Ḥamūya suggests that the Real is utterly unfathomable in Its Essence, knowable only through Its manifestation in created entities. As projections of the Real, however, these entities qua entities lack essential qualities of their own and cannot be known in and of themselves. Instead, they are differentiated through (a) their relationships with the Divine Essence, (b) their relationships with one another, and (c) the context according to which all of these relationships are understood. Because the Real continually manifests Itself in new ways, these webs of association and the vistas from which they may be considered are in constant flux. Through a clever manipulation of the phenomenal and conceptual dimensions of the Arabic letters, Ḥamūya provokes readers to experience and reproduce these limitless possibilities within their own bodies.

In what follows, Saʿd al-Dīn deploys an extended meditation on the letter kāf to explore how the Real becomes hidden by the very mechanisms that make It manifest. He writes:

(i) The three alifs of “Verily, I am” are veiled by the letter kāf. For all of existence, the kāf of the garment “Be!” is the word of the human being.

(ii) Each of those alifs is composed of three points. These are: hearing, seeing, and speaking; the Spirit of God, the Holy Spirit, and the Faithful Spirit; the singular, seizing, and existing [soul]; the commanding [soul], accusing [soul], and the [soul] at rest; the knowledge of certainty, the essence of certainty, and the truth of certainty; prophecy, sainthood, and divinity; Adam, Eve, and [their] children; the sun, the moon, and the planets; the sea, the river, and the fountain; and the essence, the attributes, and the names.

(iii) Kāf is the garment (kiswat) of these universals (kulliyyāt). However, when the existence of kāf (kawn-i kāf) becomes evident, the kāf of unbelief (kāf-i kufr) rises up to the kāf of contemplation (kāf-i fikr) and becomes unveiling (kashf gardad). The appearance of the hidden treasure (kanz-i makhfī) becomes manifest on account of kāf’s shift from “I was” (kuntu) to “Be!” (kun). In kāf, the totality of generated beings (mukawwanāt) are contingent (mumkin) and brought into being (mutakawwan) in a way that is manifest and hidden, secret and open. Kāf is thus the form of alif’s shaykhliness (shaykhūkhiyyat)—i.e., when it has become three dots (sih nuqṭa gashtih ast). “When the alif reaches full maturity (shākha), it becomes kāf.” So, in reality, the storehouse of the hidden treasure (bih ḥaqīqat makhzan-i kanz-i makhfī) is kāf.

(iv) The kāf of the word [kāf] (kāf-i kalimat) is the being of the Real (kawn-i ḥaqq). The alif of kāf is unity (aḥadiyyat). Its fāʾ is uniqueness (fardiyyat) and supremacy (fawqiyyat), and qāf and kāf are the latitude lines of the tiny bead (ʿirḍ-i balad-i karār). These are called Shayṭab and Qasṭab, for each of the two have a single meaning.

(v) So, the qāf of potency and power (qudrat wa-quwwat) is kāf and the firm dwelling (qarār-i makīn), the clear speech (qawl-i mubīn), the alchemy of happiness eternal (kīmīyā-yi saʿādat-i abadī), and the endless arrival (iqbāl-i sarmadī) are all within it. The universal perfection (kamāl-i kullī), particular sufficiency (kafāyat-i juzʿī), magnificent grandeur (kibriyā-yi kabīr), the core of things (kunh-i ashyāʾ), the return of grace (karūr-i niʿmat), and the nobility of the whole (karm-i jumlat) come from [kāf], as does the removal of covers (kashf-i sutūr). This is just as [the Prophet] said, “Within the son of Adam is a morsel of flesh (muḍgha); when it is sound, so is the rest of the body, and when it is corrupt, so is the rest of the body. Certainly, this [morsel] is the heart (al-qalb).”7

Conceptually speaking, the passage outlines the simultaneous manifestation and concealment of God’s Essence through creation. While Ḥamūya’s thematic focus is fairly standard Sufi fare, a close attention to the poetics of his text illuminates performative strategies that engage readers in an active process of meaning making.8

As he explores the tension between the manifest and the hidden, Saʿd al-Dīn manipulates kāf as a sound, repeating and reorienting the letter qua name (kāf) and the letter qua phoneme ([k]) in diverse permutations. Working through paragraph 3, for example, we hear kāf-i kiswat-i kull-i kawn kalimat-i insānī ast, kāf kiswat-i īn kulliyyat, kawn-i kāf, kih kāf-i kufr, kāf-i fikr, kashf, kanz, kāf-i kuntu, kun. The same paragraph finds Ḥamūya slipping between kāf and neighboring palatals khāʾ, gāʾ, and qāf, offering readers kashf gardad, kanz-i mukhfī, shaykhūkhiyyat, nuqṭa gashtih, shākha, and finally bih ḥaqīqat makhzan-i kanz-i makhfī. In paragraph 4, he breaks the letter kāf into its constituent parts, linking the letters kāf, alif, and fāʾ to specific Divine Attributes. The letter qāf in the Attribute of supremacy (fawqiyyat) inspires another series of shifting palatals in paragraph 5: qāf, qudrat, quwwat, kāf, qarār-i makīn, qawl, kīmīyāʾ, iqbāl, kamāl, kafāya, kibrāya, kunh, karūr, karm, kashf, qalb.

What should we make of these dizzying alliterative sequences? Echoing the Qurʾānic imperative to read/recite (iqraʾ!), Ḥamūya’s text demands embodied engagement. Read aloud, the constant repetition of kāf, its constituent parts, and adjacent palatals engages readers' organs of speech and audition, allowing them to hear and feel how cosmic principles are continually broken apart, transmuted, reoriented, and refashioned in new contexts through the Divine Self-Disclosure. To heed the shaykh’s call is thus to activate his performative language and transform one’s body into a site of dynamic meaning making.

Ḥamūya couples his sonic play with myriad allusions and citations. Apart from clear references to the Qurʾānic verse “Verily, I am God” (Q. 28:30), paragraphs 1 and 3 allude to the passages in which God creates through speech—that is, “He says 'Be,' and it is” (e.g., Q. 2:117, 3:47, 3:59, 6:73, 14:60). Paragraph 3 likewise includes an allusion to the hidden treasure ḥadīth, a favorite among medieval Sufis. As the letter kāf moves from the word kuntu (“I was”) to the word kun (“Be!”), the hidden treasure—i.e., the Real—becomes manifest, albeit cloaked in the garment (kiswat) of creation and, ultimately, the letter kāf itself.9 On the one hand, Ḥamūya’s citation adds an affective dimension to the Divine Self-Disclosure (“I was an unknown treasure, yet longed to be known”), encouraging readers to understand the play of manifestation and concealment through the drama of emotional experience. On the other, the shaykh’s Qurʾānic allusions intimate a link between readers' own voices (here, repeating the letter kāf) and the divine speech (kun) through which the entire cosmos is brought into being.

Saʿd al-Dīn textures his discussion with allusions to concepts from outside the Qurʾān and ḥadīth corpora as well. Paragraph 2, for example, sketches manifestations of the Primordial Point (i.e., the Real) while also drawing upon such philosophical terminology as universals (kulliyāt), generated creatures (sing. mukawwan), and contingent beings (sing. mumkin).10 The shaykh sprinkles the passage as a whole with an array of obscure concepts and technical terms—malakūt and jabarūt, the maturation and visual transformation of the letter alif, Shayṭab and Qasṭab, universal perfection and particular sufficiency—, many of which are mentioned, but never fully explained. Finally, paragraph 5 includes a brief reference to al-Ghazālī’s (d. 1111) Alchemy of Happiness (Kīmīyā-yi saʿādat), whose opening chapters probe the nature of the human heart.11 Here, the microcosmic heart mirrors the macrocosmic kāf as a storehouse for the entirety of the Divine Attributes. The allusion emphasizes the human being as the focal point of creation, the nexus through which cosmic processes (and lettrist strategies) intersect. Ḥamūya further underscores this intertextual allusion with a ḥadīth outlining role of the heart in the body, deploying the citation as a way to propel his readers toward his a sustained discussion of the heart in the following section of the text.

The passage as a whole links sounds and feelings to dynamic cosmic processes, encouraging readers to experience Self-Disclosure in their own bodies. He presents a series of lettrist riffs on kāf, both as a letter and as a sound, coupling this sonic and sensory play with continual allusions. Each word becomes a site of endless interpretation, leaving readers without any solid conceptual mooring. At the same time, by spinning these shifting forms and associations around a single set of symbols, sounds, and sensations, Ḥamūya balances the experience of dynamic transformation and limitless possibility with a sense of sonic and sensory unity.

In short, Ḥamūya shows his readers how the Real only becomes accessible through the relationships that arise among created entities. Here, ontology and epistemology are inextricably intertwined. As is the case with the cosmos, there is no knowable “object” at the core of Saʿd al-Dīn’s ontological speculation—no doctrine or dogma, no grand fact, no positive creed to be confirmed or denied. Knowledge of the Real—like the Real Itself—is only accessible through the infinite, dynamic, and incommensurable relationships that arise among created entities. Through performative language, he brings the underlying qualities of these relationships to the forefront of readers' experiences. For Ḥamūya, to truly know is to cultivate a unified subjectivity made manifest through an infinite expressive potential; to become a creative nexus through which the Self-Disclosure is continually reenacted. The shaykh does not cobble together a cache of facts, but teaches us to recognize (and reproduce) the Real in all Its registers. Ḥamūya is writing being; not as a kind of Platonic mimêsis, but as a creative production of Reality enacted through the mechanisms of creation itself.

Looking Forward?

Even among his contemporaries, Saʿd al-Dīn’s work stands out for its deconstructive ethos and radical openness to interpretation.12 While his colleagues flaunt their authority by dazzling readers with the totalizing scope of their own interpretive sensibilities, Ḥamūya parochializes their work by opening up his words to the creative imagination of his readers. He is keenly aware of the dialogic interplay between subjectivity and meaning, and develops creative methods to exploit the endless interpretive potential that different readers could bring to a single text. Essentially, Ḥamūya’s writing self-consciously reconfigures itself to subvert any sense of conceptual or interpretive closure whatsoever. By denying his audience a totalizing hermeneutical vision, Ḥamūya forces each reader to generate new abstract and experiential possibilities within their minds and bodies. It is in dialogue with the sensibilities of his readers, then, that Ḥamūya’s language unfolds as boundless play; through their living, breathing, and speaking bodies that his words become expressions of a limitless Reality.

With Ḥamūya as a guide, Lost in a Sea of Letters explores the global efflorescence of medieval Sufism as a function of its rich internal diversity, relational potential, and endlessly contested possibilities. I suggest that the shaykh and his interlocutors also contribute to ongoing conversations in religious studies, the history of knowledge, and the humanities more broadly. Their generative insights can help expand the epistemological range of contemporary approaches to knowledge, opening avenues through which to explore the social, corporeal, and affective qualities of our own intellectual frameworks. What might marking and interrogating these dimensions of our epistemologies reveal about our own universalizing pretensions and the relationships of power they aim to fix? How might our unmarked practices of reading, writing, and even feeling authorize particular knowing subjects while erasing others? And finally, how might our epistemologies and identities be entangled with those from which we so desperately wish to tear ourselves free?

Author Bio

Cyril Uy is Assistant Professor of Religion at James Madison University. He has received a BA from Yale, Master’s degrees from Cambridge and Stanford, and a PhD from Brown. Cyril has collaborated with Wilferd Madelung on an Arabic critical edition and English translation of the Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ’s “Epistle on Spiritual Beings,” published with Oxford University Press in association with the Institute of Ismaili Studies in 2019. As a PhD candidate, he served as the inaugural Mellon Teaching Fellow in Global Islamic Studies at Connecticut College in New London. His dissertation, entitled “Lost in a Sea of Letters: Saʿd al-Dīn Ḥamūya (d. 1252) and the Plurality of Sufi Knowledge,” analyzed Ḥamūya’s deconstructive ethos and radical openness to interpretation as a window into the generative epistemological potential of medieval Sufism. His current book project builds upon this research, exploring the global efflorescence of medieval Sufism as a function of its rich internal diversity, relational potential, and endlessly contested possibilities. Focusing on strategies of deconstruction and play in avant-garde Sufi treatises, the project illuminates how an active cultivation of difference could thrive as a robust approach to social and intellectual competition.

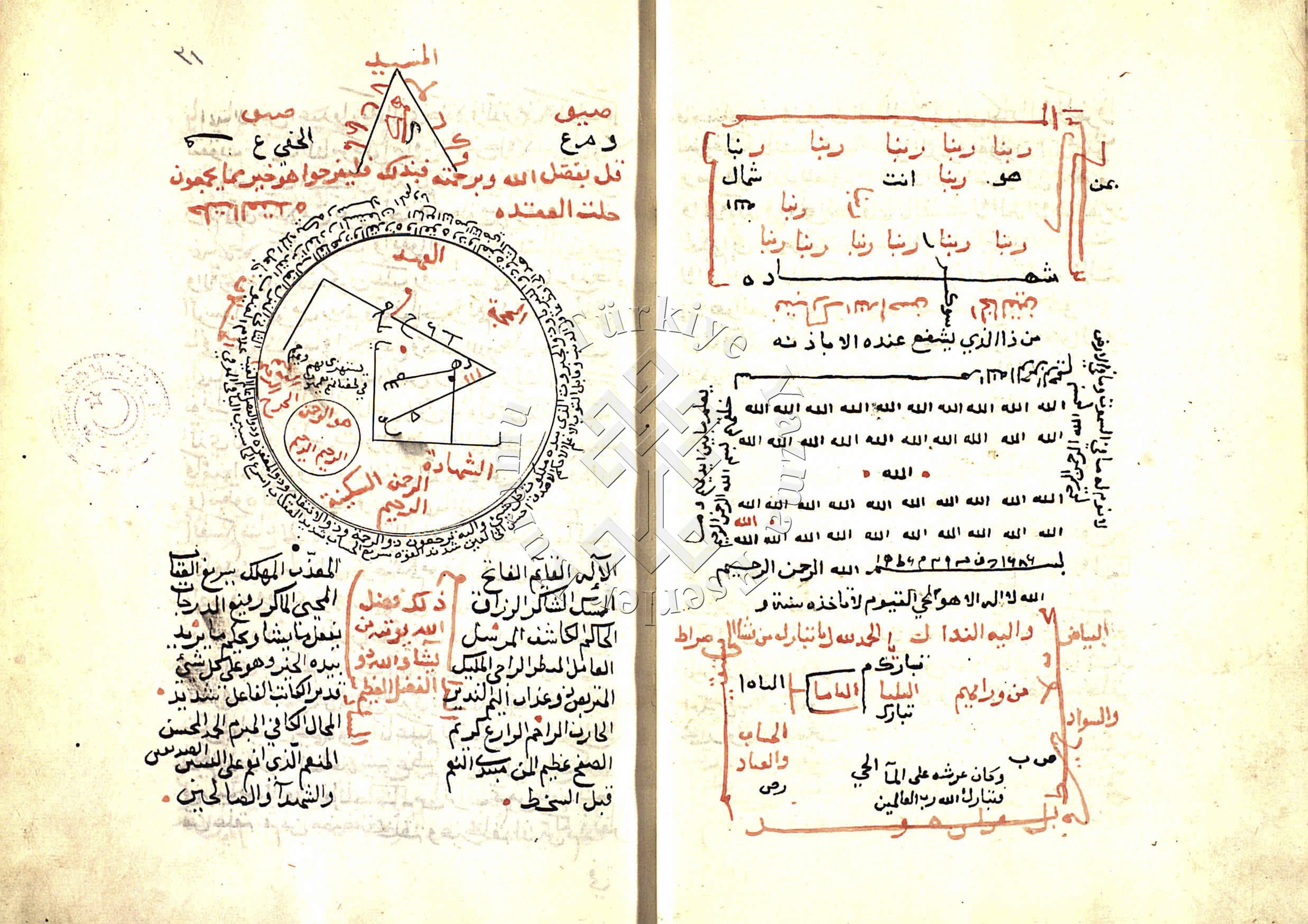

Image: Sajanjal al-arwāḥ (Süleymaniye MS Carullah 1541, fol. 30b-31a)

-

These Ḥamūya family shaykhs include, for example, ʿImād al-Dīn Abū Fatḥ ʿUmar ibn ʿAlī (d. 1181), who was appointed the first Chief Sufi (shaykh al-shuyūkh) of Greater Syria and Ṣadr al-Dīn Abū al-Ḥasan Muḥammad (d. 1220), who presided over Damascus before being appointed Chief Sufi of Egypt. Ṣadr al-Dīn, in turn, passed the position down to his four sons—ʿImād al-Dīn ʿUmar ibn Muḥammad (d. 1238/1239), Kamāl al-Dīn Aḥmad (d. 1242), Muʿīn al-Dīn Ḥasan (d. 1246), and Fakhr al-Dīn Yūsuf (d. 1249)—and a few of his grandsons. See Saʿīd Nafīsī, “Khāndān-i Saʿd al-Dīn-i Ḥamawī,” Kunjkāwīhā-yi ʿIlmī wa Adabī 83 (1950), 11-13 and Nathan Hofer, “The Origins and Development of the Office of the ‘Chief Sufi’ in Egypt, 1173-1325,” Journal of Sufi Studies 3, no. 1 (2014): 1–37. ↩

-

For Ḥamūya’s training under Kubrā, see Ghiyāth al-Dīn Ḥamūya (fl. 14th c.), Murād al-murīdīn, ed. S.A.A. Mīr-Bāqirī Fard and Z. Najafī (Tehran: Muʾassasat-i Muṭālaʿāt-i Islāmī-yi Dānishgāh-i Tihrān - Dānishgāh-i Makgīl, 2011), 13-15. For Kubrā’s ijāza to Saʿd al-Dīn, see Najm al-Dīn Kubrā, Ijāza li-Saʿd al-Dīn Ḥamūya, Istanbul, Süleymaniye Kütüphanesi, Murad Buhari MS 318, fols. 57b-58a and Ghiyāth al-Dīn, Murād, 17-19. For Ḥamuya and Kubrā’s disciples, ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Jāmī (d. 1492), Nafaḥāt al-uns min ḥaḍarāt al-quds, ed. Mahdī Tawḥīdī-Pūr (Tehran: Kitābfurūshī-yi Saʿdī, 1958), 424-425 and 428-430. For Ḥamūya and Suhrawardī, see Ghiyāth al-Dīn, Murād, 11, 26-27 and Faṣīḥ Aḥmad ibn Jalāl al-Dīn Muḥammad Khwāfī (d. 1445), Mujmal-i Faṣīḥī, ed. Muḥsin Naṣrābādī (Tehran: Asāṭīr, 1966), II.290, 319. For Ḥamūya, Ibn ʿArabī, and Ṣadr al-Dīn Qūnawī, see Ghiyāth al-Dīn, Murād, 28-31; Jāmī, Nafaḥāt, 429; Ṣadr al-Dīn al-Qūnawī, al-Fukūk fī asrār mustanadāt ḥikam al-Fuṣūṣ, ed. ʿĀsim Ibrahīm al-Kayyālī (Lebanon: Books - Publisher (Kitāb - Nāshirūn), 2013), 55; and Ḥamūya’s letter to Ibn ʿArabī in Saʿd al-Dīn Ḥamūya, Sharḥ bāl wa-rashḥ ḥāl (Risāla ilā Muḥyī al-Dīn Ibn ʿArabī), Los Angeles, UCLA Library, Special Collections, Caro Minasian MS 32, fols. 99-108 and idem, “Makātīb-i Saʿd al-Dīn Ḥammūʾī,” in Jashn-Nāma-yi Ustād Sayyid Aḥmad Ḥusaynī Ashkūrī, ed. Aḥmad Khāmih-Yār and Rasūl Jaʿfaryān (Tehran: Nashr-i ʿIlm, 2013), 482-483. For Nasafī’s explicit references to having served Ḥamūya in Khurāsān, see e.g., Nasafī, Kitāb al-Insān al-kāmil, ed. Marijan Molé, 3rd ed. (Tehran-Paris: L’Institut Francais de Recherche en Iran / Editions Tahuri, 1993), 316, 321. For Nasafī’s framing of his work vis-à-vis that of Saʿd al-Dīn, see Nasafī, Kashf al-ḥaqāʾiq, ed. A. Dāmghānī (Tehran: Bungāh-i Tarjuma wa Nashr-i Kitāb, 1965), 7. ↩

-

See Nasafī, Kashf al-ḥaqāʾiq, 7 and Lloyd V. J. Ridgeon, ʿAzīz Nasafī (Richmond, Surrey: Curzon, 1998), 11. ↩

-

See ʿAlāʾ al-Dawla Simnānī (d. 1336), Chihil majlis-i Shaykh ʿAlāʾ al-Dawla Simnānī, ed. Najīb Māyil Hirawī (Tehran: Intishārāt-i Adīb, 1987), 172-176; Marijan Molé, “Les Kubrawīya entre Sunnisme et Shiisme aux huitième et neuvième siècles de l'Hégire,” REI 29, no. 1 (1961), 100-102; Jamal J. Elias, The Throne Carrier of God: The Life and Thought of ʿAlāʼ ad-Dawla as-Simnānī (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1995), 43-44; and Giovanni Maria Martini, ʿAlāʾ al-Dawla al-Simnānī between Spiritual Authority and Political Power: A Persian Lord and Intellectual in the Heart of the Ilkhanate, Islamicate Intellectual History 4 (Leiden: Brill, 2018), xvi-xix. ↩

-

Matthew S. Melvin-Koushki, “The Quest for a Universal Science: The Occult Philosophy of Ṣāʾin al-Dīn Turka Iṣfahānī (1369-1432) and Intellectual Millenarianism in Early Timurid Iran” (PhD dissertation, Yale University, 2012), 200 ff.; Shahzad Bashir, Messianic Hopes and Mystical Visions: The Nūrbakhshīya Between Medieval and Modern Islam (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2003), 79-80; and Muḥammad Nūrbakhsh, “The Risālat al-Hudā of Muḥammad Nūrbakš (d. 869/1464): Critical Edition with Introduction,” ed. Shahzad Bashir, Rivista Degli Studi Orientali 75, no. 1/4 (2001), 107-108. Incidentally, Ḥamūya’s text is the only work besides the Qurʾān that Nūrbakhsh mentions by name. ↩

-

See Matthew Melvin-Koushki, “MAḤMUD DEHDĀR ŠIRAZI” in EIr and Maḥmūd Dihdār Šīrazī (fl. 1576), Ḥall al-rumūz fī sirr al-kunūz, Ankara, Milli Kütüphanesi, Milli MS 2706f-1. ↩

-

Saʿd al-Dīn Ḥamūya, al-Miṣbāḥ fī al-taṣawwuf, ed. Najīb Māyil Hirawī (Tehrān: Mawlā, 1983), 81-82. ↩

-

I adapt the concept of performativity from Bissera Pentcheva’s work on medieval Byzantine icons. See eadem, The Sensual Icon: Space, Ritual, and the Senses in Byzantium (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010). ↩

-

The hidden treasure ḥadīth is widely attested in Sufi works, yet absent from major ḥadīth collections. The ḥadīth is commonly formulated as follows: “I was an unknown treasure, yet longed to be known.” See also Ibn ʿArabī’s citation in Muḥyī al-Dīn Ibn ʿArabī, Fuṣūṣ al-ḥikam, ed. Abū al-ʿAlā ʿAfīfī (Beirut: Dār al-Kitāb al-ʿArabī, n.d.), 203 and idem, Ibn al ʿArabi: The Bezels of Wisdom, trans. R.W.J. Austin (Mahwah: Paulist, 1980), 257. According to Moeen Afnani, the oldest attestation of the ḥadīth can be found in ʿAbd Allāh Anṣarī’s (d. 1089) Generations of the Sufis (Ṭabaqāt al-ṣūfiyya). See Moeen Afnani, “Unraveling the Mystery of the Hidden Treasure: The Origin and Development of a Ḥadīth Qudsī and Its Application in Ṣūfī Doctrine” (PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 2011), 10. ↩

-

The triplicate projections of the point outlined in the Miṣbāḥ most closely resemble the scheme presented in The Book of the Point (Kitāb al-Nuqṭa). See Saʿd al-Dīn Ḥamūya, Kitāb al-Nuqṭa, Istanbul, Süleymaniye Kütüphanesi, Şehid Ali Paşa MS 1364, fols. 76b-77a. ↩

-

Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī, Kīmīyā-yi saʿādat, ed. Ḥusayn Khidīw-Jam (Tehran: Sharikat-i Intishārāt-i ‘Ilmī wa Farhangī, 2001), 15 ff. ↩

-

I use the term deconstructive to mark Ḥamūya’s penchant for destabilizing ostensibly coherent systems, exploiting irreconcilable contradictions, and relishing in the ebullient productivity of language. ↩