Jane Mikkelson on Seeing the Unseen in Early Modern Persian Poetry

Written on October 22nd , 2021 by Jane Mikkelson

(The following is adapted from Jane Mikkelson, “Color’s Fracture: Translating Fugitive Experience in Early Modern Persian Poetry,” in The Routledge Companion to Persian Literary Translation, eds. Pouneh Shabani-Jadidi, Michelle Quay, and Patricia J. Higgins; 2022.)

In a couplet by Nasir ‘Ali (d.1697), a Persian poet from Sirhind in northern India, readers are shown what it can be like to escape from the phenomenal world of color and experience something typically veiled from view—a colorless realm of reality that lies beyond matter, beyond time:

I, Nasir ‘Ali, am light of spirit.

You do not know

the worth of wings:

I can travel, soaring

through that other world

with color’s fracture.1

Declaring himself to be an unencumbered soul, Nasir ʿAli praises his own ability to “travel” through “that other world” (sayr-i anjahan). What enables his flight is “color’s fracture.” But what exactly does it mean for color to break? How can someone travel to another world through color’s fracture—and why would they want to in the first place? Although this phrase is not attested in modern dictionaries, shikast-i rang (“the fracture of color”) occurs frequently in early modern Persian poetry. Emerging likely at some point during the sixteenth century, it gained traction especially among seventeenth-century poets associated with India (‘Urfi, Qudsi, Salim, Hazin, Sa’ib, Nasir ‘Ali, Bedil, Arzu, and others). While earlier poets use a version of this phrase to linger elegiacally over discrete biographical moments of past loss—moments when “color broke” (shikast rang)—the phrase “color’s fracture” (shikast-i rang) pivots towards more positive forms of fugitive experience, where the fact of having faded, or vanished, or broken allows readers to see an unseen world.

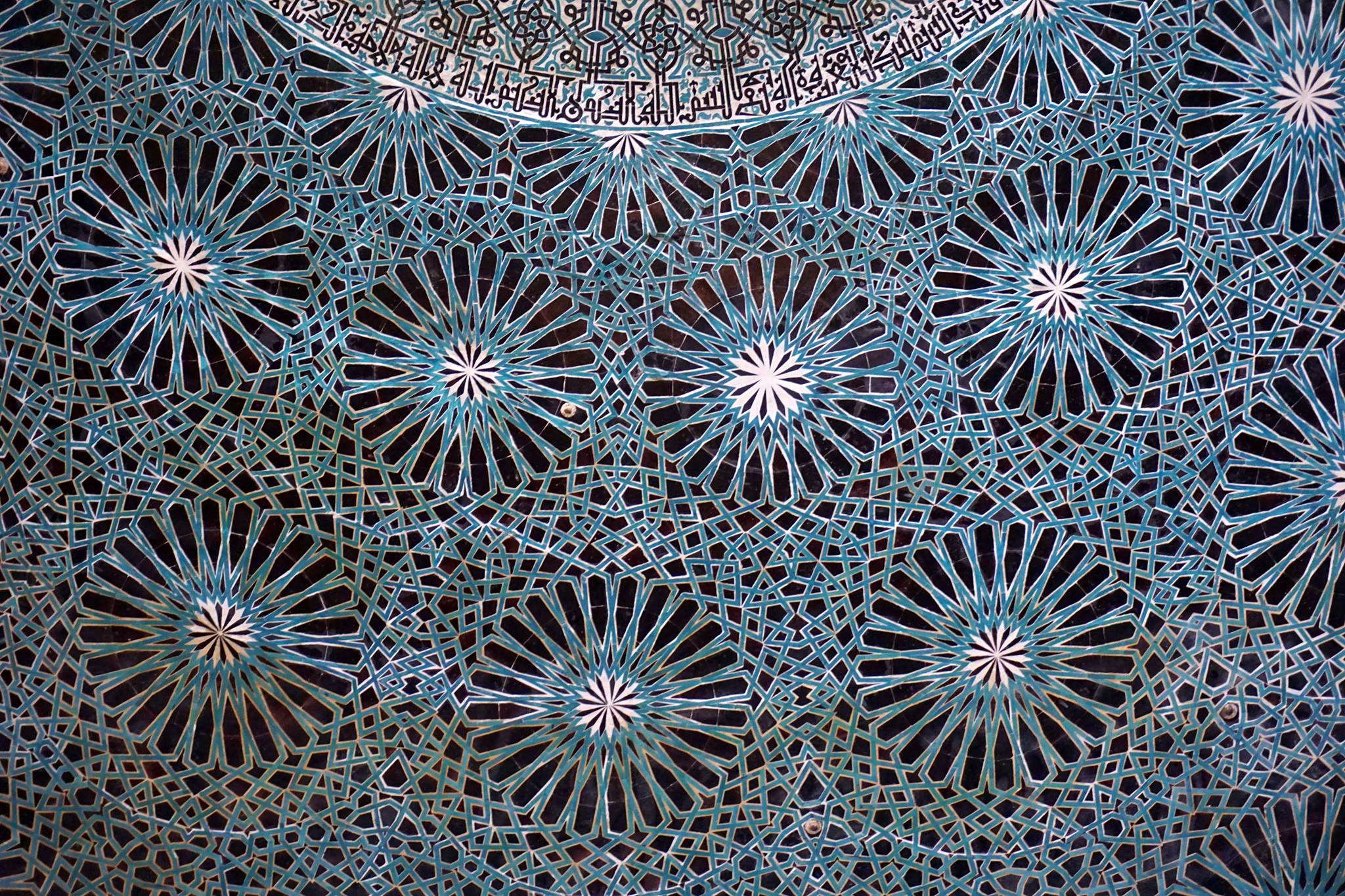

Fascination with the fracture or absence of color often leads poets to dwell on the pallor of celestial events: the blank white page of dawn, the Milky Way, a ghostly new moon. These suggestively pale phenomena communicate something worth understanding, as in the following couplet by the poet and philosopher Bedil of Delhi (d.1721):

You saw the Milky Way

even color’s fracture

can be comprehended

Those who have no self

can cross the turning skies

exploring them

with pale slipping steps 2

Or take this hemistich, also by Bedil, which traces the impossible one-winged flight of a new moon:

My flight

encompasses the sky

like a new moon

flying

on a single wing 3

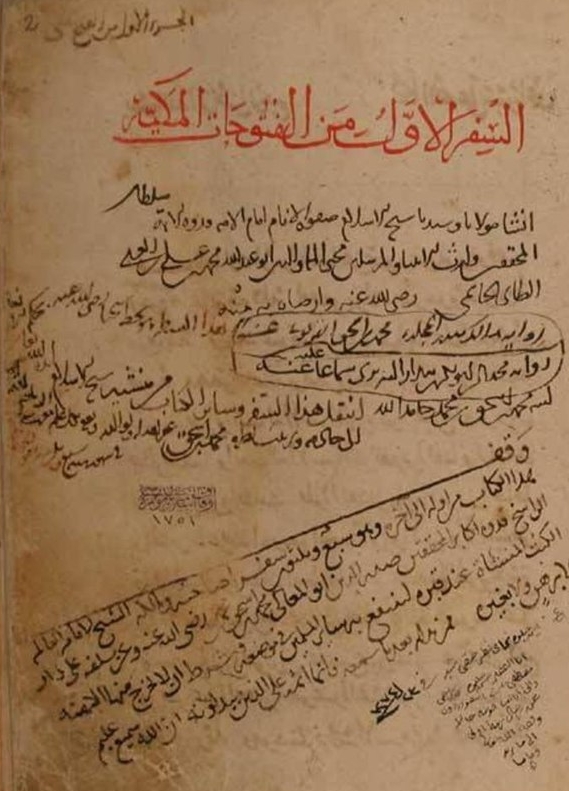

Why were these poets drawn to color’s fracture? When encountering images like this, it is often necessary hunt for meaning beyond the local context of a poem. Early modern works of comparative religion are especially illuminating; in treatises and translations, scholars draw upon ideas from different traditions—such as Islam and Hinduism—as they make creative attempts to work out a practical philosophy of perception with cross-confessional appeal. For instance, Dara Shikoh (d.1659), the Mughal scholar-prince whose projects of comparative religion were profoundly influential in early modern South Asia, writes in his Persian translation of the Upanisads that the world-soul (atma) pervades all appearances (surat-ha), being “in every place, such that no place is empty of it.”4 Even though this fundamental substance is singular, “because of maya [illusion],” it appears in many forms; these forms are so multitudinous that their number is beyond reckoning. Only capable persons like gnostics (‘arifan) and monotheists (muvahhidan) are able to “escape from the illusory prison of the body” and arrive at an understanding of this underlying world-soul, which Dara Shikoh describes in Sufi-Islamic vocabulary as “the light of the essence” (‘ayn-i nur-i zat). Another passage in Dara Shikoh’s Persian Upanisads explains how this divine light passes from oneness into multiplicity: after experiencing a desire “to become more,” this light takes on “many different forms” by generating the elements (fire, water, earth), which mix to make everything we see in the world. These three fundamental elements are associated with three primary colors: fire with redness, water with whiteness, earth with blackness.5 In another work by Dara Shikoh, The Confluence of the Two Oceans, a remarkable treatise in which he attempts to align the core doctrines of Islam and Hinduism, color and colorlessness appear in a chapter on prophethood. He identifies three kinds of prophets: those who see God with their own eyes, like Noah; others, like Moses, who hear God’s voice; and finally, prophets like Muhammad, who both hear and see divine truth. Muhammad’s prophethood combines the resources of both senses, and Dara Shikoh writes that Muhammad’s form of prophethood is superior because it embraces both “color” and “colorlessness” (rang and birangi).6

Bedil employs strikingly similar language in his long poem Gnosis (‘Irfan) in his discussion of how divine light passes from singular colorlessness into a world of colorful multiplicity. Addressing readers directly, he commands them to “see and understand” (bibin u bidan). But it is not obvious how vision and understanding should collaborate. Bedil recognizes that, in untutored form, vision is inadequate to the task of understanding true reality, to seeing what Dara Shikoh calls the “colorless light” (nur-i birang) of the divine in the world of appearances. So how can the unseen be seen? Instead of urging his readers to shun the world of color, Bedil spurs them forward, urging them to “take a journey, explore—see what colors that light contains” (using the same word found in Nasir ʿAli’s couplet uses for exploratory journey, sayr).7 Bedil does not neglect the affective dimensions of exploration. He repeatedly says that this kind of visual experience should ignite passion (shauq), delight in beauty (husn), and result in mirth (naz).

At a literal level, color is one of the most basic attributes of items in the world, available to everyone without conscious effort. And color’s absence seems at first to be just that—an absence; now you see it, now you don’t. But early modern Persian poets are rarely interested in description as an easy means to a visual end. Indeed, they often go to great lengths to ensure that complex ideas like color’s fracture cannot be instantly visualized. When readers encounter a difficult image, when they can’t immediately see the idea—they are forced to really think. Poetry like this invites introspection. Readers begin to ask themselves: Can I trust my senses? How stable are my experiences? Is it possible for me to access higher forms of reality? Through indeterminate, resonant ideas like color’s fracture, poets prompt readers to explore connections between vision, knowledge, cosmology, imagination, and enlightenment. As they spend time in difficult poems, readers abstract themselves momentarily from the colors of the phenomenal world. Poetry allows readers to soar beyond ordinary experience—perhaps even to discover “another world” beyond color, to see the unseen.

Author bio

Jane Mikkelson studies comparative literature, Persian literature and Islamic thought, translation studies, and theories of literature, with a particular interest in comparative projects that bridge early modern Near Eastern, South Asian, and European literary and religious cultures. Her work has appeared in Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, University of Toronto Quarterly, Journal of South Asian Intellectual History, Modern Philology, and elsewhere. Her current book project examines practices of lyric meditation in the early modern Islamic world. Jane received a joint PhD from the University of Chicago in South Asian and Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations in 2019, and she is currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Virginia (College Fellows).

Copyright Jane Mikkelson, 2021.

Further Reading

Supriya Gandhi. The Emperor Who Never Was: Dara Shukoh in Mughal India. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020.

Jonardon Ganeri. The Lost Age of Reason: Philosophy in Early Modern India 1450-1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Phyllis Granoff. “Coloring the World: Some Thoughts from Jain and Buddhist Narratives.” Religions 11 (2019), 1:9.

Prashant Keshavmurthy. Persian Authorship and Canonicity in Late Mughal Delhi: Building an Ark. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Domenico Ingenito. Beholding Beauty: Sa’di of Shiraz and the Aesthetics of Desire in Medieval Persian Poetry. Leiden: Brill, 2020.

Justine Landau. De rythme et de raison: lecture croisée de deux traités de poétique persans du XIIIe siècle. Paris: Presses de la Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2013.

Paul E. Losensky. Welcoming Fighani: Imitation and Poetic Individuality in the Safavid-Mughal Ghazal. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1998.

Stefano Pello. “The Portrait and Its Doubles: Nasir ‘Ali Sirhindi, Mirza Bidil and the Comparative Semiotics of Portraiture in Late Seventeenth-Century Indo-Persian Literature.” Eurasian Studies 15.1 (2017), 1-35.

Image: Detail from A Night Scene from Shiva Puja, ca. 1760 (The Cleveland Museum of Art).

-

Sabukruham ‘ali qadr-i par-u-balam namidani / tavanam az shikast-i rang sayr-i anjahan kardan. Nasir ‘Ali Sirhindi, Divan-i Nasir ‘Ali (Kanpur: Munshi Naval Kishor), 91. ↩

-

Kahkashan didi shikast-i rang ham fahmidanist / bikhudan dar laghzish-i pa sayr-i gardun karda-and. Bedil Dihlavi, Kulliyyat (Tehran: Intisharat-i Talaya), 2010/2011, Ia:720-721. ↩

-

Chu mah-i nau bi yik bal asiman sayr-ast parvazam. Ibid, Ib:1042. ↩

-

“…dar hama ja ast va hich ja az u khali nist.” Prince Muhammad Dara Shikoh, Sirr-i akbar: Upanishad [The Greatest Secret: the Upanishads], ed. Tara Chand and S.M. Reza Jalali Naini (Tehran: Taban Press), 1957, 42. ↩

-

“An hast [yigana va bi-hamta] khvast ki man bisyar shavam, surat-ha-yi gunagun shud.” Ibid, 134. ↩

-

Prince Muhammad Dara Shikoh, Majma’ al-bahrayn [The Confluence of the Two Oceans], ed. M. Mahfuz-ul-Haq (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, 1998 (1929)), 100-101. ↩

-

Sayr kun ta chi rang darad nur. Bedil, Kulliyyat III:58. ↩