Mariam Sabri on Seasons of Sentiments, Tracing Temporality from the Indic Bārahmāsā as a Method for Islamicate Intellectual History

Written on September 25th, 2021 by Mariam Sabri

Bārahmāsā (twelve seasons) poetry was in popular parlance across early modern India. Heard and sung from rural to regnal realms, the genre denoted folk logics of monthly time and synchronized seasons with sentiments. Each season embodied peasant and littoral women’s ecological and economic anxieties and rationalities. Reflective of vernacular cosmology, the bārahmāsā is a rare and rich archive. In this essay, I offer a method for writing Islamicate intellectual history from below by animating the subaltern sensibilities emanating from seasonal poetry and permeating astronomical texts and regional architecture.

The bārahmāsā informed temporal conception for a set of entangled time-tellers. One such example from 17th century Lahore was a cosmopolitan Persianate astronomer by the name of Sher-i Muḥammad Hazārī. Hazārī was a devotee of vernacular mystical poets in Punjab who in turn were the ventriloquist of the anxieties, rationalities and sensibilities of peasant and sailor women. In 1621, Sher-i Muḥammad Hazārī puzzled over interpreting, systematizing, and synchronizing seasonal time across three cosmological systems—Indic, Persian and Arabic. His conundrum emanated from the absence of a stable or singular ontological category of seasons in pre-colonial India—organically fluctuating between four, six and twelve. In a cosmomorphic verse Hazārī sketched an evocative relational image of these three seasonal frames:

When the Sun is in Sarat̤ān (Cancer) it is the month of Sāwan

Know that Leo in Murdād’s means the month of Bahādarūn

The Indic monsoon month (Sāwan) overlaps with the Persian month of Tīr while the sun is in Sarat̤ān (Cancer). Next, the Persian month of Murdād coincides with the late Indic summer month of Bahādarūn while the Sun is in Leo. The verse metaphorically represents the passage of months and seasons during the solar year in North India—where Cancer’s ascendance precedes the monsoon and culminates into the 31-day month of August, a length similarly conceived in Persian and Indic calendars.

Seasonal synchronicity was a crucial endeavor. In the tradition of preceding astronomers, Hazārī knew that conjointly making meaning of these overlapping seasonal frames, had broader implications for relating to the environment, agricultural activity, teaching about the cosmos and casting horoscopes to predict fortunes. Ecologically, Eurasia’s Little Ice Age (1550-1850) was particularly crucial, causing Central Asian migrations southwards and the drought of 1554-1556 in South Asia that was accompanied by the failure of the monsoon and dearth of food crops. Ontologically, the month and season were not separate in the Indic cosmos, even as they were ascribed the Persian unit of māh (month) since at least the 12th century. Mughal investment in the exact sciences—specifically astronomy— alongside ontological flexibility and epistemic versatility was necessitated by the empire’s need for economic resilience and renewal in response to environmental and political change.

The bārahmāsā (twelve seasons)—with a long pre-modern history and modern after-life—was one of the main modes of discourse on seasons that emanated from peasant and littoral experiences and emotions and infused elite spaces and sensibilities. The bārahmāsā allowed for immersive inhabitation of natural knowledge—measuring and telling seasonal time in units of emotion i.e. grief, abandonment, desire and longing. The highest form of this emotion was the suffering of the virahinī—the abandoned peasant woman pining for her lover and biding time—the passage of seasons—for his return. In the mystical rendition of bārahmāsā poetry by Sufi saints this suffering represented separation from the divine beloved—which could only be alleviated through ultimate union (fanāʼ). Suffering through separation was an epistemic journey in itself—a path to knowing through inhabiting love—and only attaining complete illumination through union. The bārahmāsā is one amongst many Islamicate poetic genres—where the suffering of carnal love (ishq-i majāzī) was a metaphor for the pursuit of divine love (ishq-i ḥaqīqī). True knowledge—and its painful pursuit—was intrinsically tied to true love. Emotion was a necessary precursor for reason.

In the bārahmāsā, Sāwan—the monsoon season—represents a cycle of renewal and replenishment with the abundance of rain. However, it is not a neat promise of either. This is mirrored in the genre by the virahinī’s expectation but frequently unmet desire for the return of the beloved in the aftermath of renewal.

In the month of Sāwan a stream runs from the eyes

It doesn’t stop for even a day

The land’s potholes and wells have been filled with rain

The land is wearing a new, precious dress

The kohl of the eyes does not stay

The mīnā weeps on the hour (ghaṛī ghaṛī) and it fades away

In the monsoon the moon elopes with Alork

The entire stream is run by the mīnā’s eyes

The downpour of the eyes is as hail

The thread of the necklace has decayed in this water

The Sāwan which you have bathed in

Is the Sāwan that flowed from the eyes of the mīnā

Oh Creator (sarjan) tell folks that this is mīnā’s ill-fate

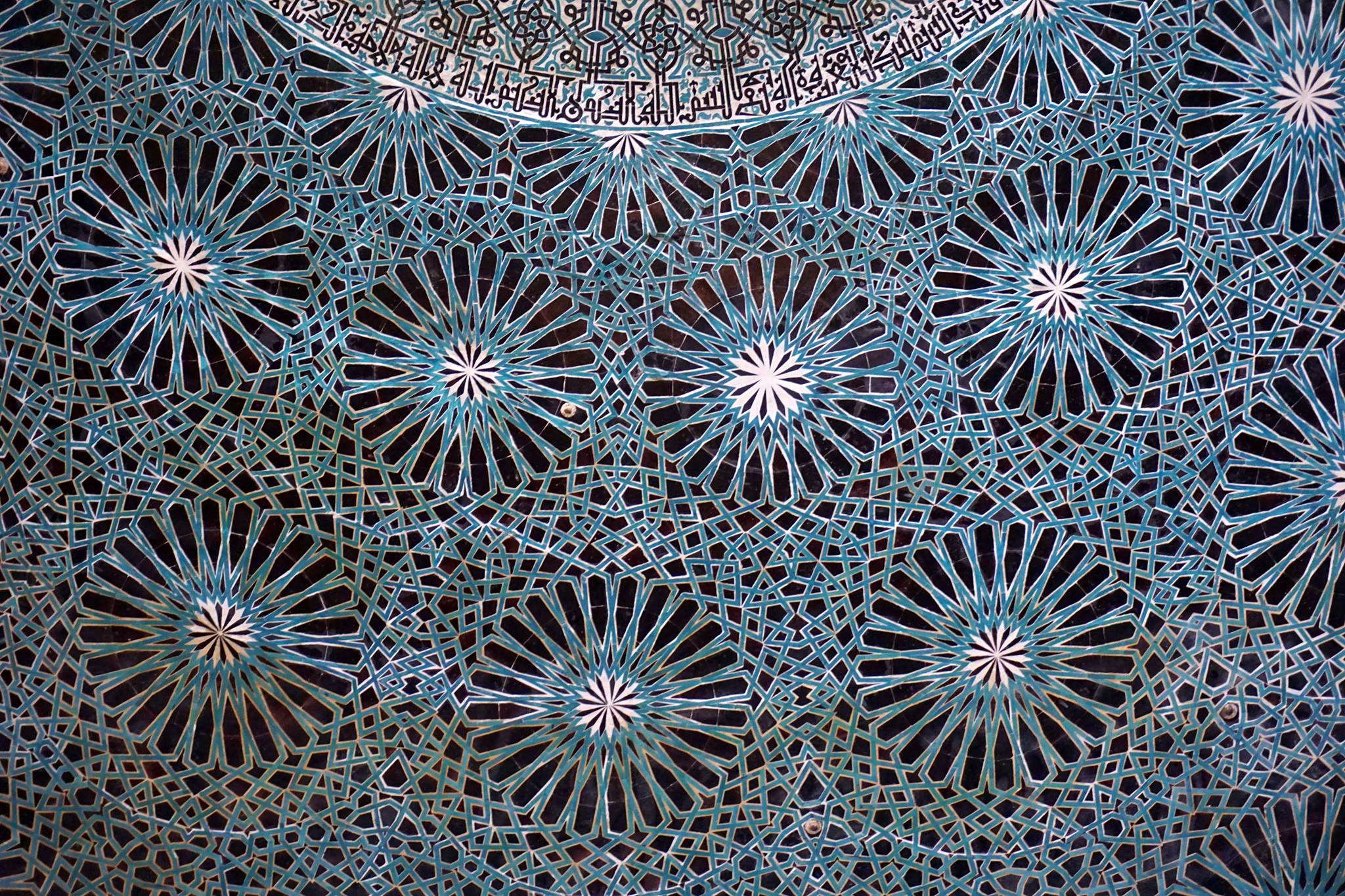

Seasonal time and hourly time are interwoven in this meditation on the monsoon by Mulla Daud—a Sufi saint of North India and the ancestor of the revered saint and scholar Abdul Haq Dehlavi who served the Mughals. Sāwan is jointly measured through units of the peasant woman’s emotions—prolonged stretches of grief and transient bouts of joy. Even as her weeping is constant, it is temporalized in the Indic hour (ghaṛī ghaṛī). Here, the image of a water-clock comes to mind, absorbing the rainfall of the mīnā’s grief. Yet, Sāwan as the season of renewal is a recurrent trope (the land is wearing a new, precious dress). This is captured in a parallel visual idiom of the bārahmāsā—in Mughal and Rajput miniature paintings. Pictorial depictions of monsoon rain reflected a thirst for environmental and economic prosperity.

The work of the poets and artists of the bārahmāsā elevated the collective aesthetic, affective, economic, and material hopes of many communities in a climate of uncertainty and risk. This ecology shaped economic realities that influenced the possible configurations of love and family in the early modern period. And even if peasant women’s hopes were realized in an expression of rain, perhaps they had already been dashed by precarity as men traveled far and wide for military and seasonal employment in the months preceding the monsoon. The wait for the monsoon reduces all animate actors—human and non-human—to their base primal desires which alongside represents the soul’s thirst to unite with God. Beings in all the kingdoms of nature (mawālid-i s̤alās̤a)—animal, vegetable, and mineral—are parched for love and sustenance. The image renders the grief of the virahinī in the dark sky, and snake-like lightning-struck clouds with a poisonous downpour. While the peacocks sit below the sky seemingly unperturbed, a halo-rimmed Krishna approaches the gopīs. In contrast to the menacing grief of the sky, and the playful distance of Krishna and the gopīs, the canals are overrun and replenished. The earth rejoices while the lovelorn Radha grieves inside giving us a glimpse of her emotions through the crackling sky. The betrayal of the monsoon does not wash away the pain of separation for the virahinī. In fact, the replenishment of the parched terrain shows the powerful place the rain clouds occupy in both peasant and elite imagination.

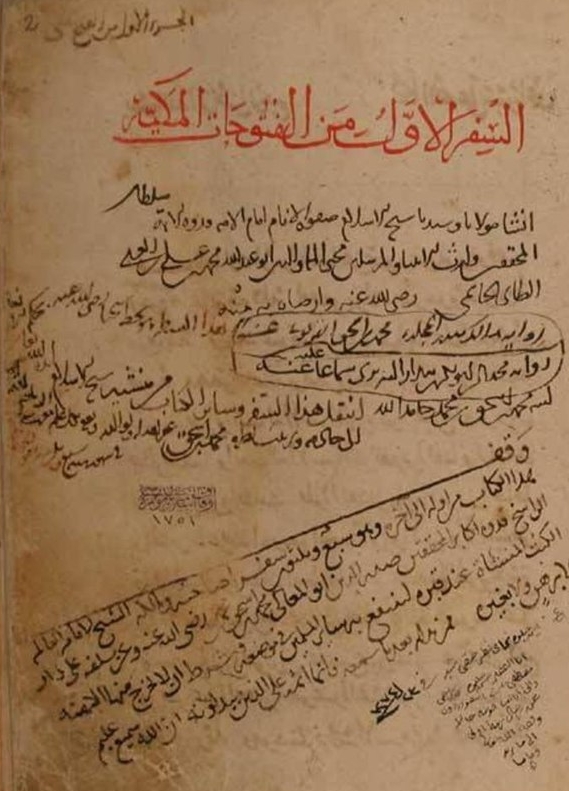

The temporal logics of the bārahmāsā routed through mystical poetry became absorbed in Hazārī’s astronomical treatises. In Aḵẖtar-i Hazārī (Hazārī’s Stars), Hazārī offers an emblematic way of syncing seasons and in the process making meaning of cosmic time and environmental rhythms. Hazārī conceived seasons as Persian units and months in Indic sub-units. The months of Kātik and Mārgarha fall under Faṣl-i Ḵẖarīf (Autumn), Pohi and Chet under Faṣl-i Shitā (Winter), Vaiśākh, Jeṭh and Har under Faṣl-i Rabīʻ (Spring) and Sāwan, Bhādoṅ, Asāṛh under Faṣl-i Ṣaif (Summer). Especially, noteworthy is that Hazārī depicts monsoon (Sāwan) as a feature of the second season—summer (Faṣl-i Ṣaif)—in an astronomical chart correlating the annual position of constellations with seasons. The monsoon as a distinctive feature of the Indian environment—noted by the earliest Mughals—was not a stable temporal unit even as it captured inhabitants’ imaginations as a season of renewal following drought as noted earlier.

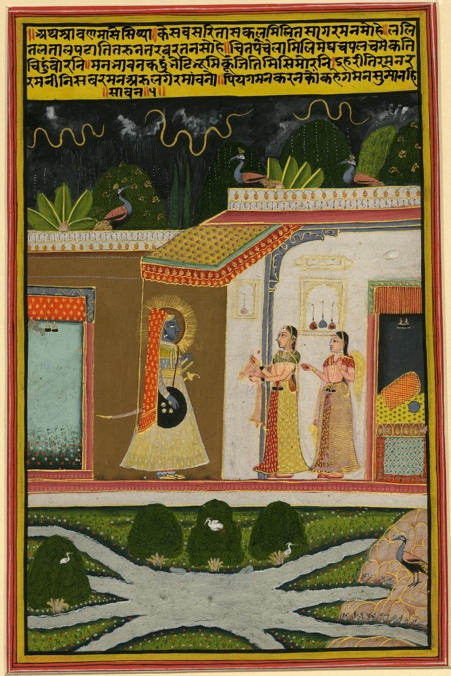

The ephemerally linked emotional world of elite and non-elite manifested in a material idiom to a lesser but notable degree in monsoon-inspired architecture. Pictured above, Badal Mahal (The Palace of Clouds) was built by Udai Singh II, the Rana of Mewar, as an extension to the medieval Kumbalgarh fort in Rajasthan. This was also referred to as the Zenāna Mahal (The Women’s Palace). Implications of divinely ordained sovereignty in the heavenly motifs of Islamic architecture have received considerable attention by Mughal historians. A palace built for women with sky and cloud motifs deserves similar attention for its social and environmental symbolism. While constructed for Rajput noblewomen, there is historical evidence that in the harem the emotional and social worlds of elite and non-elite women were intertwined. These handmaids would sing folk songs at the change of seasons (bārahmāsā), birth of children and religious festivals.

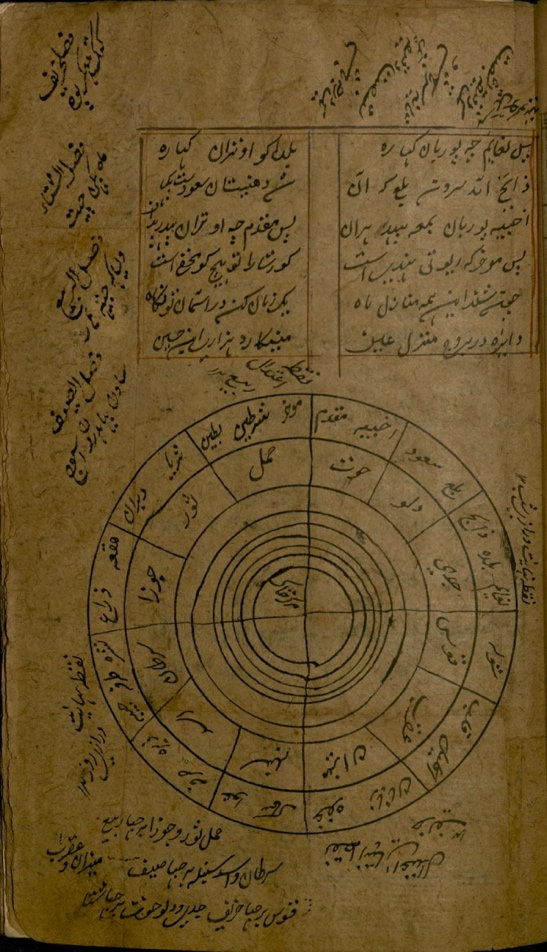

Folk and non-elite sensibilities animated elite women’s world and inspired the creation of a palace with ceilings reflecting the season of hope and renewal after a sustained period of longing and suffering. Oral histories from the palace tour guides allege that the palace was built just as much for the women as a spectacle of marvel for young princes raised by mothers and midwives. Environmentally, the cooling cerulean blue of the sky with gentle cloud motifs provided respite from Rajasthan’s semi-arid climate and stretches of brown hilly and desert terrain. The construction of the palace is contemporaneous with new developments in architecture and the advent of hydraulic technologies such as the building of canals that facilitated the creation of gardens—the Central chahārbāgh style as well as others across regional courts in the empire. Lush gardens framing the Badal Mahal reflect that it was an imperial priority to create a space of respite and renewal women and children would be able to relate to ecological aspirations reflected in familiar literary modes. Though, from this image it is evident they are not in the chahārbāgh style, and were likely relandscaped in the 19th century, ecological reimagination formed an important priority in the construction and habitation of the palace. The palace’s ceiling and pillar work in cloud and sky motifs further symbolizes the unwavering hold of the rains and the environment on the configuration of social life in early modern India.

A close assessment of the bārahmāsā reveals that the anxieties, sensibilities, and logics of peasant women can be made audible and visible even in the absence of a documentary archive. In triangulating seemingly disparate genres of sources—astronomical treatises and seasonal poetry—it appears that cosmopolitan and vernacular realms of knowledge may not have been as segmented in practice, as they are in theory and historiography. Cosmopolitan astronomy is bespeckled with temporal logics from vernacular cosmology. Promising methodological possibilities can be imagined and instrumentalized for writing an intellectual history of subaltern science at the intersection of textual, oral, and visual registers.

Author Bio

Mariam Sabri is a doctoral candidate in History with a Designated Emphasis in Science and Technology Studies. Their research specialties traverse the history of science, technology and the environment in South Asia and the littoral Indian Ocean world from 1500-2000 CE. Their dissertation contends that astronomy was the bedrock of early modern sovereignty in South Asia, enabling control of multiple temporalities, crafting narratives of cosmic truth, and configuring conceptions of the environment. Sabri’s dissertation research is supported by the Social Science Research Council, the National Science Foundation, and the Fulbright Commission. Sabri is a recent recipient of UC Berkeley’s Outstanding Graduate Student Instructor Award.

Copyright Mariam Sabri, 2021.

Images

Figure 1. Bārahmāsā: Śravaṇā with Inscription. circa 1800. Gouache Painting. British Museum. Access No: 269496001.

Figure 2. Hazārī’s Seasonal Synchronization in Aḵẖtar-i Hazārī.

Figure 3. The Palace of Clouds or Zenana Mahal in Kumbalgarh Fort, Rajasthan.

Figure 4. View of the garden (chahārbāgh) of the Zenana Mahal.