Salam Rassi on Occult Knowledge among Arabic-Speaking Christians in the Islamicate World

Written on January 10th, 2022 by Salam Rassi

Image: The Church of the Forty Martyrs, Mardin (source: Wikipedia Commons)

Those familiar with the history of Arabic philosophy and science will know of the famous Baghdad “Translation Movement” of the eighth to tenth century. In this period, Christians and Sabians, together with Muslims, participated in the translation of Greek texts into Arabic.1 Far less understood, however, is how Muslims and non-Muslims continued to participate in shared modes of scientific production in later centuries. And while scholars have long recognised that many key figures in medieval Arabic philosophy (conventionally defined) were non-Muslims, few have acknowledged this multi-confessionalism in the occult sciences.

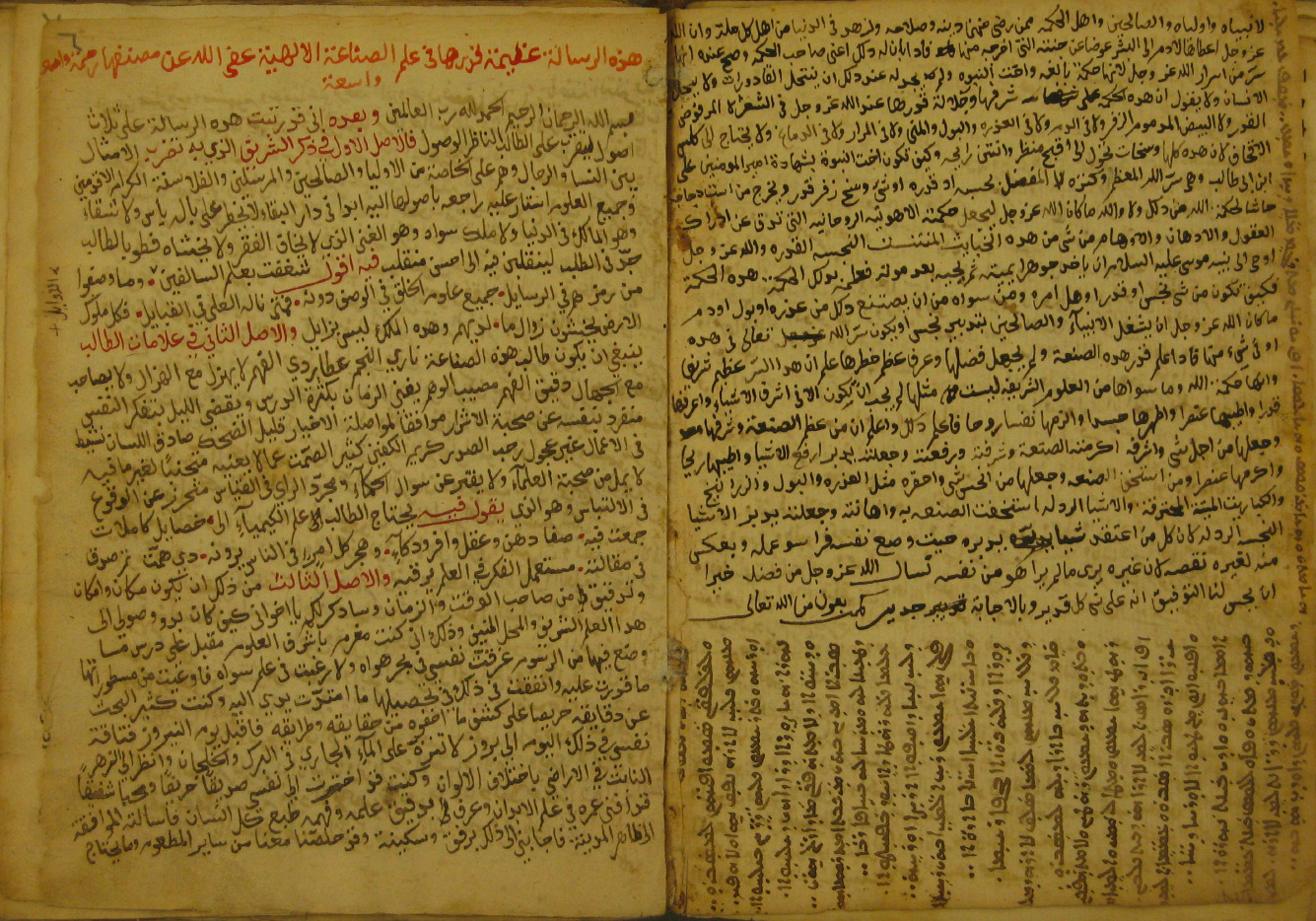

To find evidence of these encounters, one has only to look to the Arabic manuscript tradition. In addition to the Arabic script, there exist several occult scientific works written in Garshūnī, that is, Arabic written in Syriac letters. Roughly analogous to Judeo-Arabic, Garshūnī was frequently employed by Syriac-rite Christians throughout history as a vehicle for liturgical and theological literature.2 However, Garshūnī was also used to write works of Arabic literature more generally, including those that might be considered “Islamic.”

One way of understanding these intersections is through the rubric of “Islamicate” culture, a coinage of the historian Marshall Hodson (1922-1968). In his ground-breaking Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilisation, “Islamicate” describes that which does “not refer to the religion, Islam, itself, but to the social and cultural complex historically associated with Islam and the Muslims, both among Muslims themselves and even when found among non-Muslims.”3 Hodgson also speaks of a “lettered tradition … naturally shared in by both Muslims and non-Muslims.”4 This notion of a common “lettered tradition” is, I believe, a useful lens through which to study Christian involvement in the Arabic occult sciences. For it gives us sufficient scope to understand the ways in which Christians in Muslim-ruled lands participated in shared intellectual practices, while also constituting distinct confessional identities.5

A similarly useful framework comes from Sarah Stroumsa’s recent book, Andalus and Sefarad: On Philosophy and Its History in Islamic Spain. In this study of Jewish intellectualism in al-Andalus, Stroumsa identifies Arabic as not only a language of prestige but also a transconfessional koinē—“a common cultural platform for thinkers of different religious and ethnic backgrounds”. In effect, Arabic gave rise to a commonwealth of “texts, ideas, and concerns [which] were fully shared and discussed […] by philosophers and scientists hailing from different religious communities.”6 These ideas and concerns could attend to issues as varied as medicine, divine unity, God’s attributes, and the question of the world’s creation in time. However, as we shall now see, these shared intellectual concerns also extended to subjects like geomancy and alchemy.

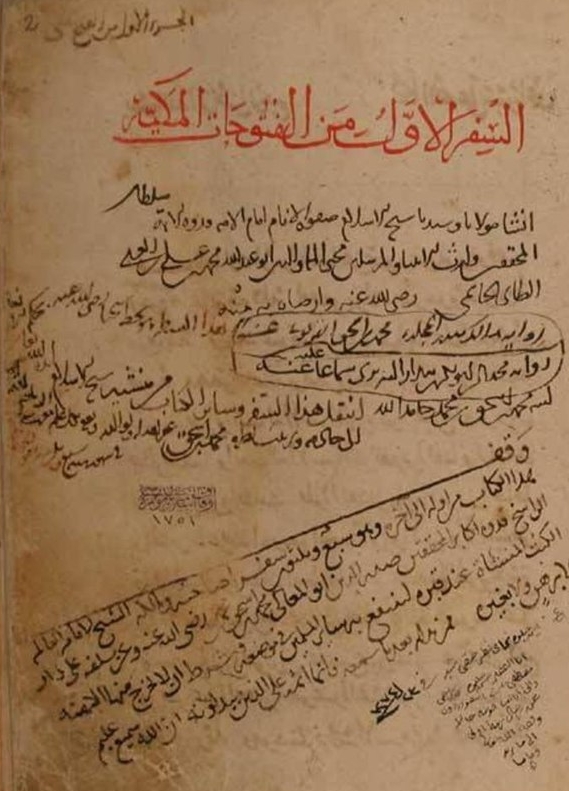

Image: Garshūnī treatise on geomancy attributed to Ṭumṭum al-Hindī (CFMM 529,

p. 307)

Image: Garshūnī treatise on geomancy attributed to Ṭumṭum al-Hindī (CFMM 529,

p. 307)

Daniel and ṬumṬum the Indian in Garshūnī Geomantic Manuals

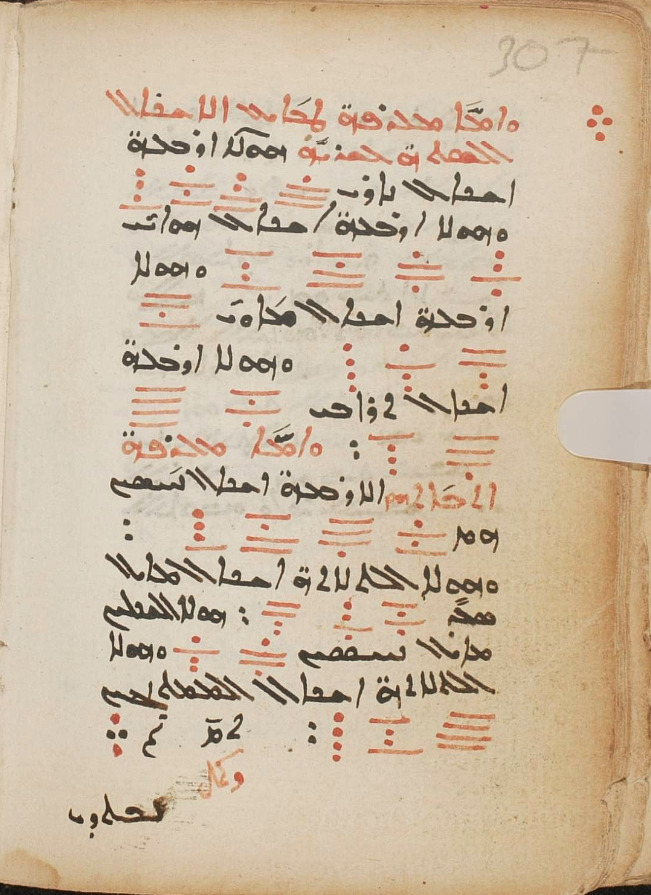

Several such works exist in ecclesiastical and monastic collections across modern-day Syria, Turkey, Lebanon, and Iraq. One such repository is the Syrian Orthodox Church of the Forty Martyrs in Mardin, recently digitised by the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (HMML).7 Here, we find two works of geomancy attributed to Ṭumṭum al-Hindī (“Ṭumṭum the Indian”), both written in Garshūnī.8 The origins of geomancy in the Islamic world are attributed to various legendary and quasi-legendary figures, the most common of whom are the archangel Gabriel and the prophet Idrīs. The latter is then said to have taught geomancy to the mysterious Ṭumṭum, an entirely legendary figure about whom little is known. The prophet Daniel is another central figure in the Islamic geomantic and astrological traditions.9 He also occurs as a principal authority in a Garshūnī manuscript of the Madākhil ʿilm al-raml from the Bibliothèque nationale de France and in one of the Mardin codices mentioned above.10

Nothing is known about the scribes of these particular manuscripts, and neither the Mardin nor the Paris witnesses are dated (though based on palaeographical evidence, an eighteenth-century date is likely). However, the occurrence of these works in Christian collections suggests a broader appeal of what is commonly assumed to be an Islamic occult science. It has been suggested by scholars that Garshūnī was used by Arabic-speaking Christians as a mark of confessional identity—a strategy that restricted certain texts to an internal audience.11 While this might be true in a certain number of cases, Garshūnī-writing also produced works that resonated beyond confessional lines.12 Geomancy, it seems, was no exception.

Image: Garshūnī copy of Madākhil ʿilm al-raml attributed to Ṭumṭum the Indian (Paris, BnF syr. 304, 22v)

Image: Garshūnī copy of Madākhil ʿilm al-raml attributed to Ṭumṭum the Indian (Paris, BnF syr. 304, 22v)

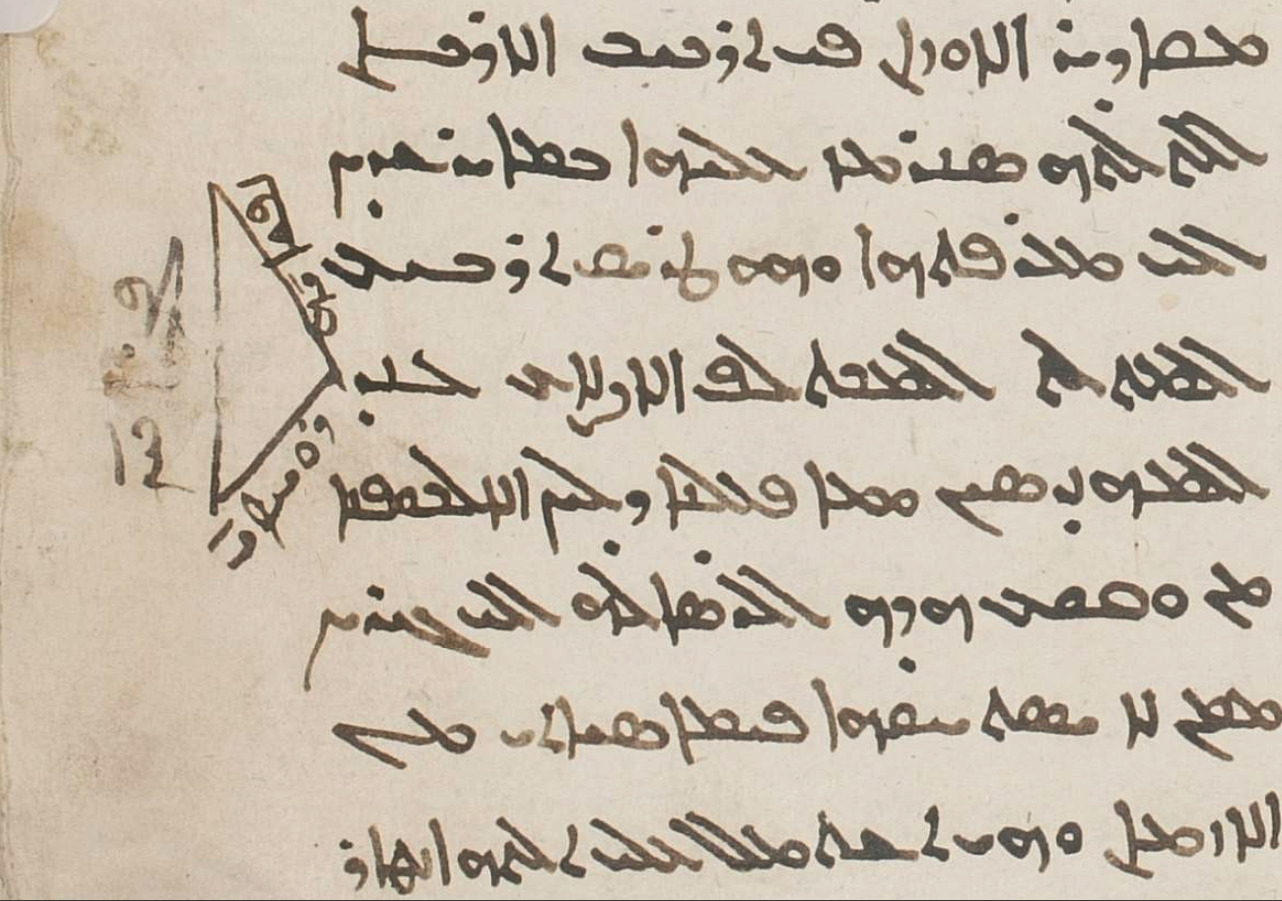

Arabic Alchemy in Syriac Christian Communities

What can the paratextual features of these manuscripts tells us about their owners? Turning now to the subject of alchemy, we encounter instances of two worlds coming together in seemingly incongruous ways. In a compendium of Arabic alchemical texts from Istanbul, we find a Syriac homily penned at the end of an Arabic-script copy of Pseudo-Majrīṭī’s Kitāb al-Rutba, a treatise on the decipherment of alchemical codes (rumūz).13 The homily is by the late-antique theologian Jacob of Serugh (d. 521) and is about Ezekiel’s vision of the chariot. Given the use of the serṭō script, it is likely that the manuscript was once owned and read by Syrian Orthodox or Maronite Christians. But why scribble a Christian theological poem on the margins of an Arabic work on alchemy attributed to a Muslim author? The reasons are unclear, but it is interesting to note that the homily occurs close to where the body text mentions that

when the scholar investigates the foundation of the [alchemical] art (al-ṣanʿa), from whatever and wherever it ought to be, he finds in his solution that it was [given] by God (mighty and majestic) to His prophets, saints, righteous ones, and sages from every nation (min kull milla) whose religion, piety, and asceticism (al-zuhd fī l-dunyā) He approved. For God (mighty and majestic) gave it to Adam for mankind as recompense for expelling him from Paradise (ʿiwaḍan ʿan jannatihi allatī akhrajahu minhā).14

Perhaps after reading this statement about alchemy as a universal science, the scribe was reminded of the following verses from Jacob’s homily:

Each man with his face set toward his place to preach the Gospel and with Simon’s confession they hasten and do not swerve: Thomas in India and Addai in Mesopotamia, Matthew in Judah and Paul among the nations of the earth.15

It is also likely that the homily was written down as a pen trial. Whatever the precise reasons, we later encounter a more direct interaction between the Syriac Christian reader and the Arabic text of the same manuscript. In the middle of an alchemical treatise by the Mamluk alchemist ʿIzz al-Dīn Aydamir b. ʿAlī al-Jildakī (fl. ninth/fourteenth c.), the writing suddenly shifts from Arabic to Garshūnī, likely to replace missing folios, since the writing later reverts to Arabic.16

Image: Syriac homily on the margins of Kitāb al-Rutba (Istanbul, Nurosmaniye 3629, 4v)

Image: Syriac homily on the margins of Kitāb al-Rutba (Istanbul, Nurosmaniye 3629, 4v)

But how did Arabic-speaking Christians interact with the occult sciences beyond reading and copying texts? As we have already noted, these manuscripts are often undated and difficult to contextualise. Nevertheless, in many early modern Garshūnī manuscripts, we find suggestions that Christians in Ottoman lands possessed a working of knowledge of alchemy, in addition to being interested readers. This is evident from the manuscript tradition of an alchemical text known as the Risālat Arisṭāṭālīs al-faylasūf ilā l-Iskandar fī l-ṣināʿa (henceforth Risāla), a systematic treatise on the making of the elixir framed as an epistolary exchange between Alexander the Great and his teacher Aristotle.17 These two figures loomed large in both the Muslim and Christian imaginaries of the medieval and early modern world.18 Yet despite some of the Risāla’s Christian associations (the author claims to have translated it from Syriac), much of the work’s alchemical principles and operations are traceable to medieval Muslim writers such as Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (d. ca. 200/815?) and Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (d. 313 or 323/ 925 or 935).19 The extant manuscripts of the Risāla itself are equally distributed between Garshūnī and Arabic script witnesses. The former were clearly read in Christian—mainly Syrian Orthodox and Maronite—circles, while the latter are found across Muslim collections from North Africa to northern India.20 As such, the text had a wide circulation not only geographically but also confessionally, spanning religions and even scripts.

Of particular interest is that the Risāla consciously avoids alchemical codes, or Decknamen. Instead, the principles of the “Noble Art” are laid out in relatively clear terms. There is one exception, however. In his letter to Alexander, Aristotle informs his pupil:

We have disclosed it (i.e. alchemy) to you and have not concealed [anything] from you in this epistle other than the measures of balances concerning the composition of the three pillars (al-arkān al-thalātha). We will symbolise these with what leads you to knowledge of them, which is by squaring a scalene triangle (tarbīʿ al-muthallath al-mukhtalif al-aḍlāʿ), according to the geometricians. We have only done so for fear that, in times to come, this epistle will fall into the hands of someone other than you, someone undeserving.21

Aristotle’s statement is somewhat opaque. However, in the margins of one of the Garshūnī manuscript from Mardin (CFMM 554), we find an illustration left by the scribe that hints at the meaning of the “squaring of a scalene triangle”. The triangle contains the following in Syriac on each of its sides: faghrō (“body”) followed by the number twenty; nafshō (“soul”) followed by the number fifteen; and rūḥō (“spirit”) followed by the number five.22 Alluded to by the scribe is a principle that was well-known in Jābirian alchemy. The variable numbers on the side of the triangle represent the differing potencies of the three metallic principles: the body is thick and course; the spirit makes the body fine and subtle; and the soul possesses a potency that lies somewhere in between.23 The diagram may have been the scribe’s way of making sense of this passage, but it also evidences a deeper knowledge of the tradition. Indeed, the triangular visualisation of the body, soul, and spirit is common throughout several Arabic alchemical manuscripts.24

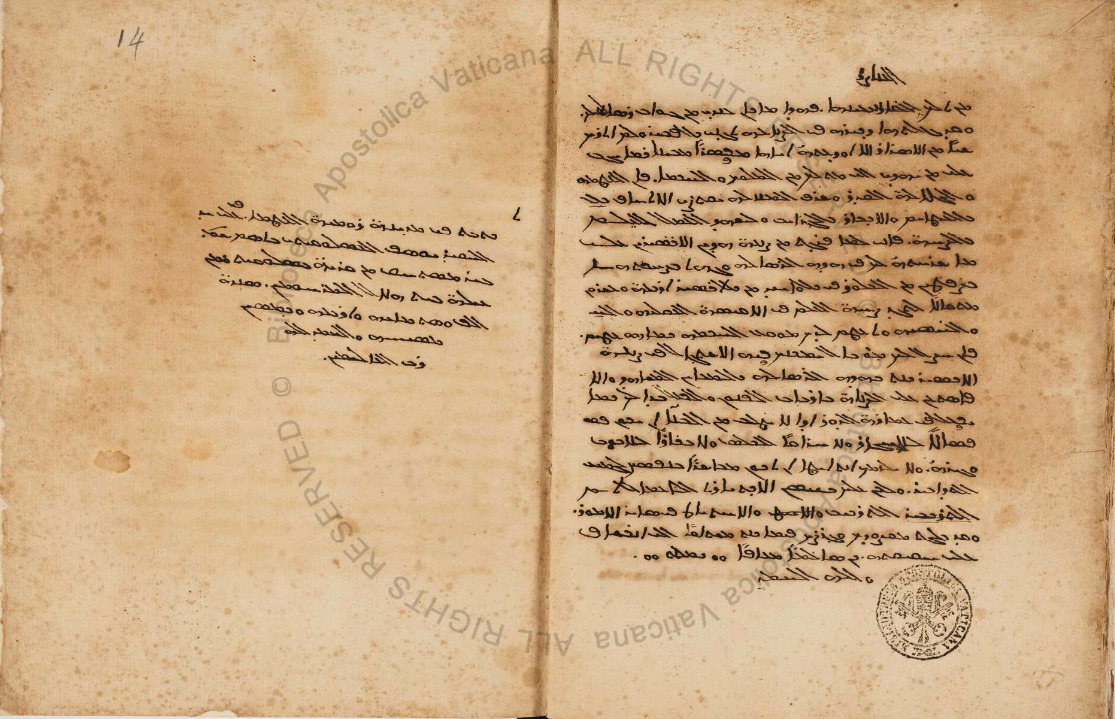

Image: Syriac illustration of the “Three Pillars” on the margin of a Garshūnī copy of Risālat Arisṭāṭālīs al-faylasūf ilā l-Iskandar al-malik fī l-ṣināʿa (CFMM 554, p. 105)

Image: Syriac illustration of the “Three Pillars” on the margin of a Garshūnī copy of Risālat Arisṭāṭālīs al-faylasūf ilā l-Iskandar al-malik fī l-ṣināʿa (CFMM 554, p. 105)

We find further evidence of an active engagement with alchemy among Arabic-speaking Christians elsewhere in CFMM 554. Before and after the pseudo-Aristotelian Risāla, there are several alchemical recipes scattered throughout the manuscript, both in Garshūnī and the Arabic script. These include directions for the making of soap, “gold clay”, and the purification of lead carbonate. The quality of the scribe’s handwriting in these recipes is drastically different compared to that of the manuscript’s systematic treatises, perhaps reflecting differences between literary composition and more ephemeral kinds of writing.25 It should be noted that similar recipes have been uncovered in other non-Muslim archives, namely those written in Judeo-Arabic from the Cairo Geniza.26 Such texts give us valuable insights into the practical as well as literary side of alchemy among Arabic-speaking non-Muslims.

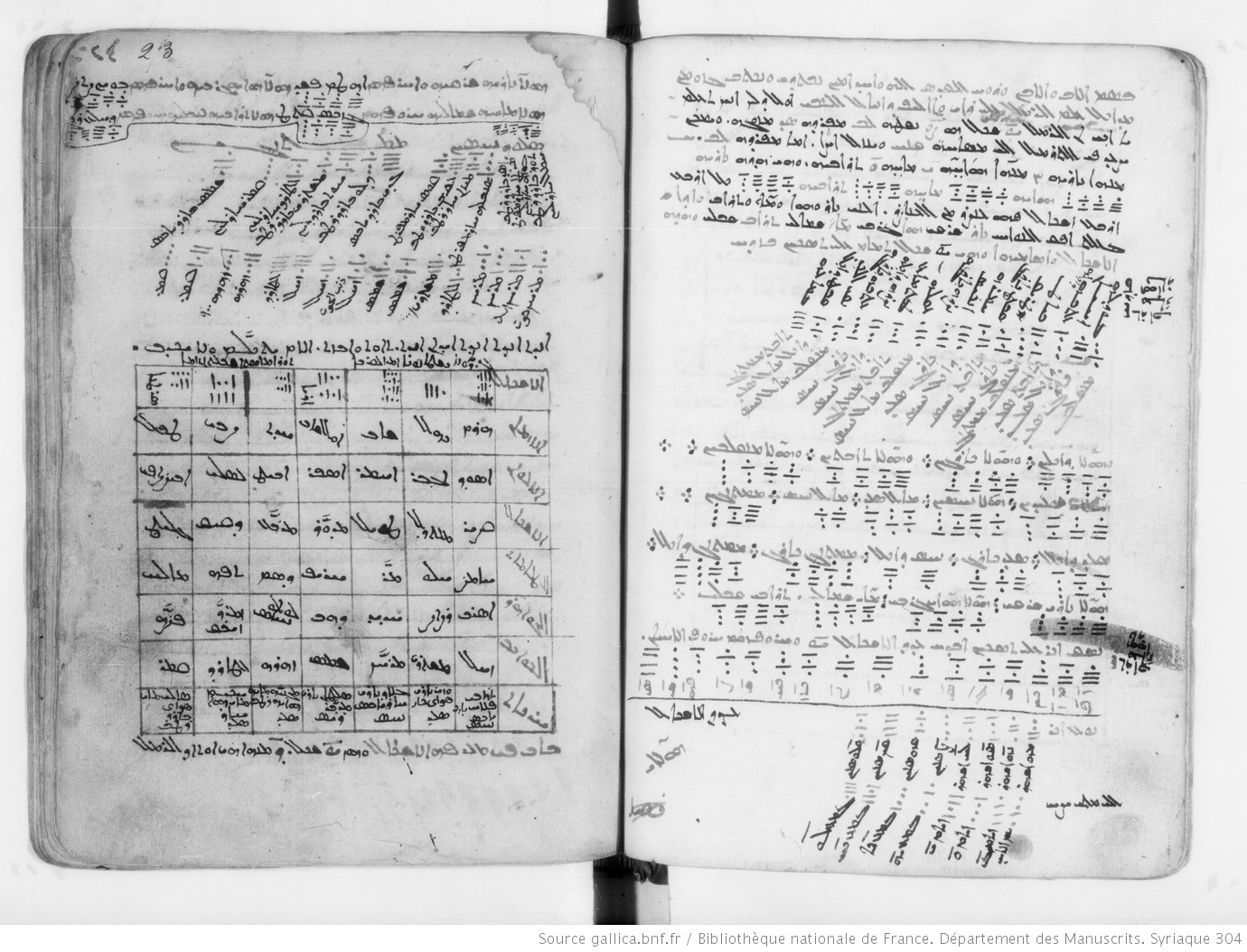

As we have seen so far, the manuscript tradition of the Risāla speaks of a transconfessional alchemical science, united in the Arabic language but set apart in script. As one might expect, these manuscripts were also set apart by social context. This is vividly illustrated in two further manuscripts of the Risāla. The first is the only dated witness to the text, a Vatican codex copied in Rome in 1654 by a Maronite deacon named Yūsuf al-Hilāl al-Baslūqītī.27 Known in Europe as Joseph Luna (a Latinised version of his name), al-Baslūqītī worked as a printer at the Propaganda Fide in Rome, where Maronites from Mount Lebanon—many of whom had previous training as scribes—found employment as translators, Arabic teachers, and copy editors.28 Other than his Garshūnī colophon, we know little about the circumstances surrounding al-Baslūqītī’s copying of this alchemical work. The second exemplar of the Risāla is in the nastaʿlīq script and was once owned by a Muslim. We can be sure of the owner’s religious identity from an ex libris by a scribe or notary, which reads: istaṣḥabahu al-faqīr Muḥammad Rāshid kātib dīwān humayun.29 Given the eighteenth-century handwriting, it is likely that the person named in this note was Meḥmed Rāşid Efendī (d. 1212/1798), a notary (dīvān kātibī) at the Ottoman Imperial Council (dīvān-ı hümāyūn) in Istanbul and later head clerk (Reʾīsü'l-küttāb).30 The backgrounds of these two manuscripts, therefore, speak of a rich and varied reception of the Risāla, read and copied as it was by a Maronite deacon in Rome and an Ottoman bureaucrat in Istanbul.

Often when we discuss Christian geomancy, alchemy, and similar topics, we tend to think of medieval and Renaissance Europe. The migration of occult knowledge from the Islamic world to the Latin West has been a subject of growing interest among scholars. But far less understood is how Christian communities in the Middle East thought about and practiced these same sciences. By studying manuscripts, we gain valuable insights into how occult figures and motifs were common property to both Muslims and Christians living in close proximity. Though separated by religion, and sometimes even script, both contexts were brought together by a shared interest in the occult sciences—sciences that might justifiably be called “Islamicate.”

Image: Colophon of Yūsuf al-Baslūqīti (AKA Joseph Luna) in Vat., sir. 209, 14r

Image: Colophon of Yūsuf al-Baslūqīti (AKA Joseph Luna) in Vat., sir. 209, 14r

Author bio

Salam Rassi is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Oxford and has held teaching and research positions at the American University of Beirut and the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library. His primary interest is in religious, philosophical, and scientific encounters between Christians and Muslims in the Middle Ages. His first book—entitled Christian Thought in the Medieval Islamicate World: Abdisho of Nisibis and the Apologetic Tradition—was published by Oxford University Press in 2021. His current research focuses on two interconnected areas: (i) the history of theological and philosophical encyclopaedism among Syriac and Arabic-speaking Christians and (ii) the Syriac reception of Avicennan philosophy. A further project involves the history of Islamicate alchemy. Much of this work centres on an unedited alchemical primer attributed to Aristotle, on which he has a 65-page article in Asiatische Studien and a critical edition and translation in progress. You can follow Salam on academia.edu and Twitter.

-

See generally Dimitri Gutas, Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early ʿAbbāsid Society (2nd-4th/8th-10th Centuries) (London: Routledge, 1998). ↩

-

For the history of Garshūnī-writing, see, Julius Assfalg, “Arabische Handschriften in syrischer Schrift (Karšūnī),” in Grundriß der arabischen Philologie. Band I, Sprachwissenschaft, ed. Wolfdietrich Fischer (Wiesbaden: Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 1982), 297–302; Emanuela Braida, “Garshuni Manuscripts and Garshuni Notes in Syriac Manuscripts,” Parole de l’Orient 37 (2012): 181–198; Joseph Moukarzel, “Le Garshuni: Remarques sur son histoire et son evolution,” in Scripts Beyond Borders: A Survey of Allographic Traditions in the Euro-Mediterranean World. Edited by J. den Heijer et al (Louvain: Peters, 2014), 107–138. ↩

-

Marshall Hodgson, The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilisation, 3 vols. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974), 1:59. ↩

-

Hodgson, The Venture of Islam, 1:58. ↩

-

For more on this point, see Salam Rassi, Christian Thought in the Medieval Islamicate World: ʿAbdīshōʿ of Nisibis and the Apologetic Tradition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021), 40–41. ↩

-

Sarah Stroumsa, Andalus and Sefarad: On Philosophy and Its History in Islamic Spain (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2019), [4–6]. ↩

-

This collection, like many others digitised by HMML, can be freely accessed online by visiting https://www.vhmml.org/readingRoom/ and searching CFMM in the HMML Project Number field. ↩

-

Kitāb al-raml taʾlīf al-shaykh al-fāḍil Ṭumṭum al-Hindī, CFMM 559 (https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/124806), pp. 275–363; CFMM 562 (https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/124231), 1-162 (beginning is wanting, though Ṭumṭum is mentioned in several places, e.g. p. 13 and p. 19). ↩

-

On these legendary authorities and others in Islamicate geomancy, see Emilie Savage-Smith and Marion B. Smith, “Islamic Geomancy and a Thirteenth Century Divinatory Device,” in Magic and Divination in Early Islam, ed. Emilie Savage Smith (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 211−276, here 2; Emilie Savage-Smith, “Geomancy,” Encyclopaedia of Islam — Three, fasc. 3 (2013): 98–101; Matthew Melvin-Koushki, “Geomancy in the Islamic World,” In Prognostication in the Medieval World: A Handbook, ed. Hans Christian Lehner, Klaus Herbers and Matthias Heiduk, 2 vols. (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2020), 2:788-93, here 798. ↩

-

Madākhil ʿilm al-raml ʿalā raʾy wa-taʾlīf Dāniyāl al-nabī Paris, BnF syr. 304, 22v–32v (https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10088698g/f25.item), dated to the 18^th^ century by Jean-Baptiste Chabot, ‘Les manuscrits syriaques de la Bibliothèque nationale acquis depuis 1874’, Journal Asiatique 9 (1896): 234–290, no. 304. At the beginning of the Kitāb al-Raml in CFMM 559, p. 275, Ṭumṭum the Indian is said to quote the teachings of the prophet Daniel (fīhi stashhada aqāwīl Dāniyāl al-nabī). ↩

-

For example, Francisco del Río Sánchez, “El árabe karshūnī como preservación de la identidad siríaca,” in Lenguas en contacto: el testimonio escrito,” Pedro Bádenas de la Peña et al. (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, 2004), 185–194, here 187. ↩

-

For an instance of this phenomenon beyond the occult sciences, see Emanuela Braida, “Christian Arabic and Garšūnī Version of Sindbad the Sailor: An Overview,” The Polish Journal of the Arts and Culture 3, no. 1 (2016): 7–28. ↩

-

Kitāb al-Rutba li-l-Majrīṭī wa-hiya mushtamila ʿalā īḍāḥ kashf al-rumūz al-ḥukamāʾ wa-aḥkāmihim al-malghūza, Istanbul, Nurosmaniye 3629, 1r–5v. Despite the title and subject matter, this work is not to be confused with the better known Rutbat al-ḥakīm attributed to the astrologer Maslama ibn Aḥmad al-Majrīṭī (d. d. 396/1005 or 398/1007) and Abū Maslama al-Majrīṭī (fl. first half of fifth/eleventh century), though more likely to be by Abū l-Qāsim Maslama al-Qurṭubī (d. 353/964); see Maribel Fierro, “Bāṭinism in al-Andalus. Maslama b. Qāsim al-Qurṭubī (d. 353/964), Author of the Rutbat al-Ḥakīm and the Ghāyat al-Ḥakīm (Picatrix),” Studia Islamica 84 (1996): 87–112. ↩

-

Kitāb al-Rutba, 5r–5v. The context here is about the use of refuse (qādhūrāt) in the making of the Philosophers’ Stone. The author is answering the criticism that the handling of impure organic products (e.g. blood, urine, and crania) necessarily makes alchemy unclean. In response, the author claims that this cannot be said of a divine science that is concerned with finding the prima materia of the elixir. ↩

-

Located at bottom margins of Kitāb al-Rutba, 5v. My translation is from Alexander Golitizin (tr.), Jacob of Serug’s Homily on the Chariot that Prophet Ezekiel Saw (Piscataway, N.J.: Gorgias Press, 2016), 92 (with parallel Syriac text). ↩

-

Kitāb al-Miftāḥ wa-nuzhat al-arwāḥ fī ʿulūm al-miftāḥ, Istanbul, Nurosmaniye 3629, 47r–186v. The shift from Arabic to Garshūnī is at 153v–154r and vice versa at 175v–176r. On Jildakī, see Nicolas Harris, “In Search of ʿIzz al-Dīn Aydamir al-Ǧildakī, Mamlūk Alchemist,” Arabica 64, no. 3, no. 4 (2017): 531–556. ↩

-

An edition of the Risāla is forthcoming from Salam Rassi and Željko Paša. For a discussion of its authorship and historical context, together with several translated excerpts, see Salam Rassi, “Alchemy in an Age of Disclosure: The Case of an Arabic Pseudo-Aristotelian Treatise and its Syriac Christian ‘Translator’,” Asiatische Studien 75, no. 2 (2021): 545–609. ↩

-

Rassi, “Alchemy in an Age of Disclosure,” 561–568. ↩

-

Rassi, “Alchemy in an Age of Disclosure,” 571–583. ↩

-

The Garshūnī manuscripts identified so far are: Rome, Vat. sir. 209, copied in Rome in 1654 (https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.sir.209); CFMM 554, pp. 74–156 (https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/124224); and Beirut, Bibliothèque Orientale 252 (https://w3id.org/vhmml/readingRoom/view/504672). The Arabic-script witnesses are Gotha or. A 85, 1v–22v; Istanbul, Carullah 1086, 56v–64v (copied in North Africa based on maghribī script); Rampur, Raza Library 4151, 1–52. In some witnesses (e.g. Gotha or. A 85, 8v), Aristotle’s response to Alexander is entitled Ṣaḥifat kanz Allah al-akbar. ↩

-

This passage is edited and translated in Rassi, “Alchemy in an Age of Disclosure,” 590. ↩

-

Diagram located at the bottom right margin of Risālat Arisṭāṭālīs al-faylasūf ilā l-Iskandar al-malik fī l-ṣināʿa, CFMM 554, p. 105. ↩

-

On this principle, see Alchemy in an Age of Disclosure,” 590–595. The “quadrupling” (tarbīʿ) of the triangle mentioned in the passage alludes to the correspondence between these three pillars and the four qualities of hot, cold, moist, and dry. ↩

-

Juliane Müller, “The Alchemical Symbols in the Manuscripts of ‘The Mirror of Wonders’ (Mirʾāt al-ʿajāʾib),” Asiatische Studien 75, no. 2 (2021): 685–722. ↩

-

Recipes located at CFMM 554, pp. 73, 157–162. ↩

-

Gabriele Ferrario, “Alchemy in the Cairo Genizah: the Nachlass of an Untidy Jewish Alchemist,” Asiatische Studien 75, no. 2 (2021): 513–544. ↩

-

al-Baslūqītī’s colophon is located on Risālat Arisṭāṭālīs al-faylasūf ilā l-Iskandar al-malik fī l-ṣināʿa, Vat. sir. 209, 14r. ↩

-

Several Arabic translations of Counter Reformation literature were printed by al-Baslūqītī; see frontispieces of Roberto Bellarmino, Dottrina Christina / al-Taʿlīm al-masīḥī (Rome: Nella Stamparia della Sacra Congregatione de Propaganda Fide, 1642); Philippus Guadagnolus, Breves Arabicæ Linguæ Institutiones (Rome: Ex Typographia Sac. Congregationis de Propaganda Fide, 1642); Francois Britius, Annalium sacrorum a creatione mundi ad Christi d.n. incarnationem. Epitome latino-arabica / Mukhtaṣar majmūʿ min al-tawārīkh al-muqaddasa mundhu khalīqat al-ʿālam ilā ʿahd tajassud sayyidinā Yasūʿ al-Masīḥ (Rome: Apud Iosephum Lunam Maronitam, 1655); We also know of several manuscripts, mostly on liturgical and theological topics, that were copied by him; see Nāṣir Jumayyil, al-Nussākh al-mawārina wa-mansūkhātuhum (Jouniyeh: Maṭābiʿ al-Karīm al-Ḥadītha, 1997–2004), 1:378–380. ↩

-

Risālat Arisṭāṭālīs al-faylasūf ilā al-Iskandar al-malik fī l-ṣināʿa, Gotha A 85, 1r. See description in Ludwig Karl Wilhelm Pertsch, Die arabischen Handschriften der herzoglichen Bibliothek zu Gotha, 5 vols. (Vienna: Kaiserl. königl. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, 1879–92), 1:150–154. ↩

-

Raşid Efendi was also the founder and sponsor of a library in Kayseri that bears his name; see Ali Rıza Karabulut, Kayseri Râşid Efendi Eski Eserler Kütüphanesindeki Türkçe, Farsça, Arapça yazmalar kataloğu, 2 vols (Kayseri: Râşid Efendi Eski Eserler Kütüphanesi, 1995). I am grateful to Tuna Artun for this information. ↩